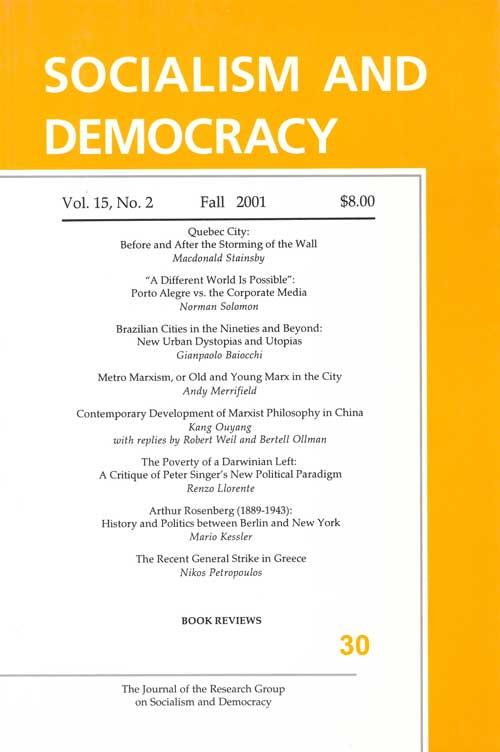

The struggle to forge an effective movement against global capital marked a new level this year with the April 20 and 21 demonstrations in Quebec City, against the Summit of the Americas. Macdonald Stainsby gives us a participant's account of the street actions as they evolved against the backdrop of the three-mile "wall of shame" which the authorities had had erected in order, as they saw it, to shield the official proceedings from another Seattle-style fiasco. Never far from the center of Stainsby's attention is the running debate over the tactics appropriate to such confrontations. His direct experiences, his reactions, and the on-the-ground responses he reports from others are all pertinent to larger questions that have been raised as to how the movement is defined (anti-corporate or anti-capitalist?), how diverse constituencies can work together, and where the "anarchist" sectors fit in.

A major boost to both the enthusiasm and the internationalism of the Quebec protests came from the consensus expressed by the more than ten thousand participants in the World Social Forum, held just three months earlier in the Brazilian city of Porto Alegre. Norman Solomon, who was present there as both a journalist and an activist, conveys something of the scope of the event as he spotlights the enormous gaps and distortions pervading its treatment in the capitalist media.

Porto Alegre's role as host-city to the first of these annual meetings-and also, next year, to the second one-stems from the exceptional impact there of the Brazilian Workers Party (Partido dos Trabalhadores-PT), which, in its four terms in control of the municipal government, has instituted exemplary processes for involving the citizenry in the details of policy-making. Gianpaolo Baiocchi situates this development in a larger context defined, on the one hand, by the catastrophic polarizing tendencies in Brazil's cities and, on the other, by a certain window of opportunity for oppositional initiatives that has been made available, at the local level, by the very instruments of neoliberalism that have inflicted so much damage on the Third World as a whole.

The city as an arena for class struggle is explored at a more theoretical level by Andy Merrifield, who tries to view urban issues from the perspective not so much of Marxism as of Marx himself. By reminding us especially of the insights articulated in Marx's early writings, Merrifield offers a view of the city that stresses its positive qualities, both as a setting from which to wage the necessary political battles and also as harbinger for a socialist future.

Given the degree to which socialism as a hegemonic objective has receded in so much of the world, and not least in China itself, it is of no little interest that Marx continues to be held in high regard in Chinese universities. Kang Ouyang presents an authoritative overview of how the reading of Marx, in that setting, has evolved to accommodate the changing official priorities-most notably in the direction of individualism and a market economy-that have characterized the years since Mao's death. Robert Weil and Bertell Ollman offer critical responses to Ouyang's presentation, drawing respectively on direct observations of contemporary China and on in-depth analysis of the implications of market primacy for any attempt to address human needs. We hope that these responses will be of particular interest to our Chinese readers, and that they will stimulate a continuing exchange of views in these pages.

In the on-going reconsideration of Marx's relevance to our times, a distinctive challenge is conveyed in the writings of Peter Singer (best known for his work Animal Liberation), who has proposed that the present-day Left, to avoid repeating historic failures, should ground its thought and practice in Darwin rather than in Marx. Renzo Llorente provides a thorough dissection of the assumptions behind this proposal, showing that it derives to a significant extent from a misreading of Marx's views on human nature.

The historian Arthur Rosenberg, whose life and work are sketched for us by Mario Kessler, has a particular place in the political tradition from which this journal has evolved. Rosenberg's best-known work, Democracy and Socialism, written in the 1930s, presented the historical evolution of those two concepts on an international canvas, in relation to the social movements which brought them to the forefront of 19th- and early 20th-century European politics. Kessler shows how Rosenberg's vocation as a historian was enriched by his role as an activist in the Socialist and Communist parties of pre-Hitler Germany.

Finally, we present Nikos Petropoulos's analysis of the recent general strikes in Greece, which went largely unreported in the United States. The issues behind those strikes, which Petropoulos examines in detail, are of worldwide resonance. Few national movements, however, have responded to them on so massive a scale.

The Editors