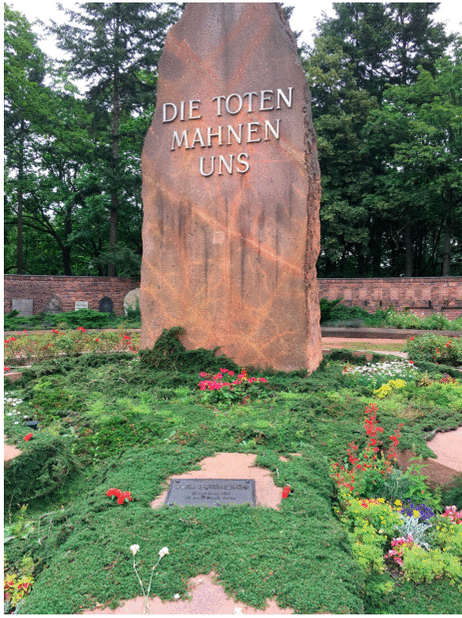

The inscription on a big rock at the cemetery in Berlin where a number of great German socialist leaders are laid to rest, reads: “Die Toten Mahnen Uns” (The dead admonish us). There are two ways to interpret this captivating phrase, regardless of its intended meaning: either that the dead urge us to remember and follow what these great pioneers did, or a warning, to learn from their experiences and follow alternative paths. Considering the historical experiences of modern socialist movements worldwide and their successes and failures, I tend to adhere to the latter.

As globalized neo-liberal capital continues to expand its dominance everywhere, notwithstanding the myriad social, political, economic and ecological crises it has created, and despite the increased resistance of progressive forces and social movements, it is crucial for the left world-wide to revisit socialist revolutions of the past. Ultra-right and reactionary populist leaders and religious fundamentalists are on the rise, taking advantage of the miseries and pandering to the grievances of growing numbers of people, while the socialist left remains in the margins. Part of this marginality is due to the continued anti-socialist atmosphere in advanced capitalist societies – despite excitements created by Bernie Sanders and Jeremy Corbyn’s brands of ‘socialism’ – along with the brutal suppression of the left in less-developed capitalist countries. Part of it is also due to the fact that a significant section of the left is dogmatically holding on to traditional paradigms and refusing to rethink past strategies. Despite efforts made by many Marxist and socialist theorists to formulate new strategies, the appeal of mass uprisings or political revolutions of any type (regardless of their eventual results) continue to persist among a section of the left, both in advanced capitalist societies and among the exiles from less-developed countries. The last major revolution of the 20th century took place in Iran, where the socialist left played a significant role in toppling the old regime, only to lose to the Islamist fundamentalists and ultimate brutal elimination, and the eradication of almost a century of the country’s cultural, social and economic developments by reactionary forces. This failed revolution forced some of us who survived to rethink revolutionary strategies, and while maintaining the grand ideals of socialism, look for alternative approaches for achieving those ends.

I need to emphasize at the outset that re-reading the great revolutionary moments of the past and a critical review of the roles played by the agents and the subjective forces, pose some dilemmas. On the one hand, questioning the critical decisions taken in a particular historical context could rightly be considered as ahistorical and at best hypothetical. Subjective decisions are not totally independent of the objective conditions of the time. Furthermore, interpretations cannot be taken as facts nor are they provable. On the other hand, if we are not to question these crucial decisions, then we have to fatalistically accept them as given. Since ultimately neither the revolutionaries nor the reformers, despite their many achievements, succeeded in attaining their final goal of establishing a socialist order, (whether or not we consider the failures of the revolutionaries as defeats ‘covered with glory’ and those of the reformists as ‘defeats without glory’ii), we need to critically revisit these failures and learn from these great historical events. The present article primarily deals with the revolutionaries, and focuses on four socialist revolutions. As will be discussed, while these revolutions occurred in very different settings, there are many similarities among them that justify the comparison.

All “socialist” revolutions (1917 Russia, 1919 Germany, 1949 China, and post-1953 and 1975 in Vietnam) emerged from previous revolutions (China’s in 1911, Russia’s in February 1917 and 1905, Germany’s in November 1918, and Vietnam’s in August 1945). All these first revolutions were a result of wars, colonial/imperialist domination or despotic rules. That is to say, not merely rooted in class struggles. This is not to downplay the existence of class contradictions and excessive exploitations of the peasantry and the nascent working class which were very effectively used by the revolutionaries to mobilize the masses, and without whose involvement, the revolutions could not have succeeded. But the external factors provided the main impetus and generated the underpinnings of the revolutions.

Furthermore, all these first revolutions were carried out by cross-class alliances of a spectrum of radical, liberal and conservative forces, and to a great extent succeeded in achieving their goals, ending foreign domination and despotic rules. The second revolutions, in turn, were led by a minority of devoted socialist revolutionaries from the new middle class and educated intelligentsia, and not just the working class, as claimed in official historiographies. In all second revolutions, the revolutionaries mobilized the masses with the aim of immediately establishing a socialist system in primarily agrarian, and to different degrees, – with the exception of Germany – pre-capitalist societies.

Marx’s notion of the social revolution was that it would come about through a “self-conscious, independent movement of the immense majority”iii. He differentiated between this “radical revolution”, which involves “general human emancipation”, versus a “political” and “partial” “revolution” which “leave[s] the pillars of the house standing”.iv The point is that all revolutions that carried Marx’s name were hardly Marxian social revolutions, despite involvement of the masses. Marx himself, also, in practice, despite his disagreements with August Blanqui over the latter’s belief in the role of a revolutionary minority leading the unprepared masses, was too excited at the time over the 1848 revolution in France and later the Paris Commune of 1871. Furthermore, he expected that the revolutionary working class, as the sole agent of transformation to socialism, would topple the capitalist system. Analyzing the capitalist system of his time, he believed that parallel to constant expansion of capitalist accumulation and centralization, “… grows the mass of misery, oppression, slavery, degradation, and exploitation; but with this grows the revolt of the working class, a class always increasing in numbers, and disciplined, united, organized …”v. In reality, however, the working class along with many other features of the capitalist system, also went through major transformations, and did not necessarily play the expected role.

Differences and similarities of the four socialist revolutions

There are certainly many differences among the Russian, German, Chinese and Vietnamese socialist revolutions. The October 1917 Russian revolution was immediately plunged into a civil war whereas the Chinese revolution of 1949 emerged from a civil war. The German revolution was immediately suppressed and the Communist party did not get a chance to establish a government and in that sense was very different than the other three. (The only reason I have included it in the present comparative piece is to show the failures of both radicals and reformers in a most advanced setting.) The Vietnamese communists, on the other hand, had to continue fighting against imperialists for almost another 30 years after their first revolution (seven years with France and over 20 years with the USA).

These revolutions were also different in terms of the objective and subjective conditions, and in their level of development of capitalism and configuration of the working population: Germany was the most advanced with a large working class population; Russia was less developed with a sizable peasantry; and China and Vietnam were the least developed, with a small working class.

Despite these and other differences, the four revolutions had many similarities. All were led by radical socialists who believed that through a forceful political revolution they could immediately establish the dictatorship of proletariat. Political differences among former allies of the first revolution intensified and radicals and moderates split and confronted each other. From the very inception, each side moved in opposite directions and the more the moderates showed conservatism and inaction, the more radicalism was fueled on the other side.

In all cases where the revolutionaries came to power, they resorted to forceful takeover of institutions and massive nationalizations, and attempts at wealth redistribution in order to fulfill their promises to the working class and the peasantry. However, confronted with the stark realities, anarchic conditions and major disruptions of production processes, and the intrigues of internal and external counter-revolutionary forces, they soon realized that they could not immediately resolve the innumerable pent-up demands. Consequently, they were forced to downplay expectations, revise their policies accordingly, and above all, suppress dissent.

Confrontations with internal and external enemies and adversaries made the new regime’s survival a top priority, forcing it to channel much of the resources needed for implementing social justice policies into securing and consolidating power. In addition to establishing powerful secret police and other means of suppression of criticism, the new revolutionary government put forward a “cultural revolution” with the aim of bringing the public in line with the party’s policies. These institutions not only suppressed dissent, but they ended up eliminating many revolutionaries who had fallen out of favour of the new rulers.

A comparative glance at some of the most significant initial revolutionary documents of these revolutions points to the optimism, and idealistic expectations of the leading figures of the revolutions. These views formed the basis of the post-revolutionary political and economic policies – policies that in confrontation with realities were constantly revised and eventually transformed significantly. Comparing the main tenets of the political systems that emerged after the second revolutions, and the economic policies put forward by the communists show the similarities in actions taken, and the ensuing consequences.

Political System and the Question of Working Class Leadership

Perhaps no other document has so drastically changed the course of a nation’s history and, in a sense, that of the world, than a “piece of paper” on which Lenin hurriedly wrote seven items to read out in a meeting, and to which he added three more theses a few days later. In the “April Theses”, Lenin stressed that “

… the country is passing from the first stage of the revolution – which owing to the insufficient class consciousness and organization of the proletariat, placed power in the hands of the bourgeoisie – to its second stage, which must place power in the hands of the proletariat and the poorest section of the peasants.” In addition to suggesting a name change for the party and establishing a new International, the theses demanded for “no support for the Provisional Government” that had come to power two months earlier, rejected the “parliamentary republic” which was the product of the February revolution, and called for “transferring the entire state power”, including the banking system, to the Soviets of Workers’ Deputies.vi

The inactions of the Provisional Government on tackling the main issues of war, land, and workers’ control had widened the gaps between different forces. The more radical the Bolsheviks became, the closer to conservatism the liberals, Cadets, SRs and Mensheviks moved. After few months of “dual power” between the Provisional Government and the Soviets, and the continuous plots by the right-wing forces, the October Revolution led by the Bolsheviks eventually toppled the Provisional Government, and in a sense the revolution moved to the “second stage” envisioned by Lenin. However, it was not clear how the “insufficient class consciousness and organization of the proletariat” as Lenin had stated, could have been resolved in only a few months. And indeed, was the power placed in the hands of the proletariat and the poorest section of the peasants? These theses soon became party policy. Aside from toppling the Provisional Government, the Constituent Assembly -- in whose elections the Bolsheviks got only 24 percent of the votes – was forcibly dissolved. The slogan, “all power to the soviets”, in practice moved all power to the Bolshevik party, and at a later stage to the “troika” (Kamenev, Zinoviev and Stalin), and eventually to Stalin himself. Years later Lenin, on his death bed, dictated letters to the party congress criticizing the Soviet government and expressed serious concerns about the concentration of so much power in the hands of Stalin.vii However, it was too late. The structure of Lenin’s “party of the new type”, banning all factions, and limiting internal democracy, which was criticized by the Old Bolsheviks in their “Platform of the 46”viii, was partly responsible for this move.

The April Theses also had explicitly put forwards a set of demands – some similar to the demands of the Paris Commune -- including “abolition of the police, the army and the bureaucracy”, and had added that “salaries of all officials, all of whom are elective and replaceable at any time, were not to exceed the average wage of a competent worker”.

These were all strong revolutionary demands, but were they implementable at that time? Were the Soviet of Workers’ Deputies at that moment capable of “controlling” the national bank and managing monetary and fiscal policies? Was the immediate abolition of police, army and bureaucracy possible or plausible? What could have been the consequences of such actions, other than pushing a large section of the new middle class to the side of the enemy? And how about the question of equating all wages and salaries? After gaining power, Lenin as the head of the “Soviet of the People’s Commissars”, had also issued new decrees, dissolving all military ranks from sergeants to generals, demanding equal pay for all, and the electability of commanders.

It did not take long for the Bolsheviks to realize that these were all too idealistic for the economy and the society’s stage of development. As John Reed explains in his account of the revolutionary events, faced with teachers and civil servant strikes, instead of dissolving the ministries, the Bolsheviks realized that they could not close down the government and only removed the very top echelons, bringing these institutions under their control. As well, the implementation of these radical changes faced resistance and created more difficulty, partly because the Bolsheviks did not have the cooperation of other parties, with the exception of the Left Social Revolutionaries, and even that was very short-lived.

Factory Committees (workers’ councils), which were one of the most important pillars of the revolution, gradually faded away. Where in 1917 they were organs of control and administration of factories, in 1918 they were transformed into state-run trade unions. Later, they became a part of the factory triad, consisting of the plant manager, the Communist Party cell secretary, and the head of the local Union. They were altogether eliminated under Stalin, when the factory triad system was disbanded and the control of factories was handed over to plant managers.

In the case of Germany, if other revolutions discussed here did not have the combined objective and subjective conditions to be qualified as a true Marxian revolution, the German Revolution of 1918 did, at least to certain degrees. This revolution occurred in a country that had produced great political minds, many of whom were alive at the time, and leading it. The Social Democratic Party (SPD) had more than one million active members before the First World War. Germany had become the second most advanced industrial country in the world, with a massive industrial working class, many of whom had created workers’ councils (Rate). With the collapse of the Empire, socialists gained control of the state power in the November 1918 revolution. Internal divisions, however, led to the failure of the revolution.

With the beginning of World War I, internal strife had intensified. The SPD, realizing that the vast majority of the working class, its mass base, supported the war, opportunistically voted for the war credits. This led to the first schism, and the left wing of the party, the Spartacists, along with revisionists and centrists separated and formed the Independent Social Democratic Party (USDP). After the 1918 Revolution, for a short while the two parties joined forces in the “Council of People’s Commissars”, but they could not agree on economic and social policies. At the same that Scheidemann of the SPD declared a parliamentary republic, Liebknecht of the Spartacists announced the establishment of the free socialist republic. Soon the Spartacists and the left wing of the USDP, angered with the right wing and their concessions to the military, separated and formed the German Communist Party (KPD).

The “Spartacist Manifesto”, “in the name of the German workers” declared that the “masses have approved our policy [and] are recognizing that the time for settling accounts with the dominant capitalist class has struck.” But it rightly pointed that “… the German working class cannot carry this great work to a successful conclusion by itself”, and while stressing that “socialism alone can heal the wounds caused by the war”, called on workers of all countries to join “a common struggle”.ix

In her speech on the “program” of the KPD to the founding congress of the party in the last day of 1918, Rosa Luxemburg followed this line and called for reconnecting with the revolutionary “measures” of the Communist Manifesto, where Marx and Engels “…believed that the immediate task was the introduction of socialism… to seize the political power of the state in order to make socialism immediately enter the realm of flesh and blood.” She emphasized that they needed to go “back to the conception which Marx and Engels abandoned in 1872 [when in the new Preface to the Manifesto they had called the measures ‘antiquated’]”.x In opposition to the long standing Erfurt program of the SPD, she rejected any separation between the “minimal” and the “maximal” program, and declared that “[f]or us there is no minimal and maximal program; socialism is one and the same thing: this is the minimum we have to realize today.” On this basis, she said that “the curtain has gone down upon the first act of the German revolution. We are now in the opening of the second act…”. Similar to what Lenin had said about the Russian working class in the February revolution, she iterated that in the November revolution “the German proletariat had behaved with intolerable ignominy and had repudiated its socialist obligations…”. Unhappy that workers’ unions had been supporting the SPD, she attacked them, saying that “... the German trade union leaders and the German Social Democrats are the most infamous and greatest scoundrels that the world has known.” She stressed that “... powers must be united in the hands of the workers’ and soldiers’ councils.”

It should be noted that such radical views were expressed by a political leader who, along with her close friend and former long-time companion Leo Jogiches, was a more moderate voice of the Spartacists/Communists. She had a strong belief in democracy and was pushing for the participation in the election of the National Assembly, but could not convince the congress not to boycott the elections. It was Rosa Luxemburg who had, from her prison cell in Germany, criticized the Bolsheviks when they abolished the Constituent Assembly in Russia.

The KPD push for a proletarian revolution was at a time when the vast majority of workers were members of either SDP or USDP. Only the Revolutionary Shop Stewards of Berlin were close to the Communists and had elected Liebknecht as their leader, but they had disagreements with the KPD and even they refused to join the party. Of the 490 delegates of the Congress of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Council who voted for the parliamentary republic rather than the council republic, only 10 were Spartacists.xi This clearly showed that even in the most advanced capitalist society of the time, the workers were not supportive of a swift move towards socialism.

The more the right-wing SPD moved towards conservatism, the more radical the left wing and the communists became. In an uprising in January 1919 which went out of control, the “Revolutionary Committee” hurriedly issued a manifesto declaring the dissolution of the government. The SPD and the counterrevolutionary forces were prepared, and brought the paramilitary Freikorps to brutally crush the revolution and kill its leaders. As one historian rightly notes, with the rise of Fascism, the German social democrats and communists who could not agree to work together were as one group sent to the concentration camps, prisons, firing squads and cemeteries.

In the case of China, in early stages, unlike Russia and Germany, there was no discussion of the leadership of the working class. Mao’s earlier vision of the nature and the stage of the second Chinese revolution was very realistic. In 1939, he wrote that the task was to carry out a “national revolution” to overthrow foreign imperialist oppression and a “democratic revolution” to overthrow feudal landlords.xii In response to the question whether the Chinese revolution was “bourgeois-democratic or a proletarian socialist revolution”, he responded that “it is not the latter but the former”. To differentiate this revolution with other bourgeois-democratic ones, he coined the “new-democratic revolution”. He explicitly pointed out that this revolution “… clears the way for capitalism on the one hand and creates the pre-requisites for socialism on the other”, and concluded that the present stage was a “stage of transition”. In relation to the development of capitalism, which at the time he implicitly recognized as necessary, Mao said “… the edge of the revolution is directed against imperialism and feudalism and not capitalism and capitalist private property …”.xiii

In 1940, the tone slightly shifted. In his “On New Democracy”, Mao, stressed that it was “the new type of revolution led by the proletariat with the aim, in the first stage, of establishing a new democratic society and a state under the joint dictatorship of all the revolutionary classes” (“the working class, the peasantry, petty bourgeoisie, and the national bourgeoisie”).

High expectations were placed on the proletariat. Similar to what Lenin and Luxemburg had said about the role of proletariat in the previous revolutions, Mao wrote the Chinese proletariat before the [1919]Movement was just “a follower of the petty bourgeoisie and the bourgeoisie”, but after that movement “...rapidly became an awakened and independent class as a result of its maturing and of the influence of the Russian Revolution.” He had also referred to the “internal opportunism of the working class” during the 1927 plots of Chiang Kai Chek.

With increasing successes either in the war against Japanese occupation, or during the resumption of the civil war, and aiming at gaining political power, few months before the October 1949 revolution Mao became more assertive in his socialist perspective. In his speech, “On the People’s Democratic Dictatorship” – which in terms of historical significance is comparable to Lenin’s April Theses or Luxemburg’s Speech in the Congress of KPD – he talked about the establishment of “classless society” and the eventual abolition of classes and state, but stressed that the immediate need was for “strengthen[ing] the state apparatus, people’s army, police and the people’s courts”. An exaggerated emphasis was again laid on the role of the working class: “The people’s democratic dictatorship needs the leadership of the working class, for it is the working class that is more far-sighted, most self-less, and most thoroughly revolutionary.” xiv

In just four years after coming to power and the establishment of the People’s Republic, Mao in the First National Plan declared that the bourgeois democratic stage of the revolution was over and the direction towards “transition to socialism” had begun. The emphasis on the leadership of the working class, however, was merely a slogan. As Frantz Schurmann notes, by 1957, the last year of the First National Plan, as a result of rapid industrialization and migration of many of the peasants to the cities, the number of the working class had risen drastically. Yet, according to Communist Party data, of the 12.7 million members of the party, only 1.7 million (less than 14 percent) were workers; The majority (66 percent) of the party members were peasants. The same data shows that number of workers were even smaller than the number of “intellectuals” in the party. The majority of these workers were also unskilled and with limited literacy and could not possibly be in the position to exercise “leadership” in the complex process of economic and social policy making.

In Vietnam, in the earlier stages there was no mention of the working class leadership. From the time of establishing Thanh Nien in the mid-1920s, Ho Chi Minh combined an anti-colonial liberation movement with a social and economic movement. “ Thanh Nien was the beginning of Vietnamese communism”.xv Ho’s emphasis in the early period, however, was more on national liberation with cross-class alliances, and less on social transformation. Until 1928 he had the full support of the organization. The 6th Comintern Congress and its radical policies, namely rejecting cross-class alliances and overemphasizing the leadership of the working class, changed the situation, leading to a split in Thanh Nien, the establishment of multiple communist parties and eventually the emergence of the Indochinese Communist Party (ICP) in 1929. The more radical elements were emboldened by the directive from the Comintern, who had claimed that Indochina had already had “an independent worker’s movement”. Ho, despite his differences, made an “appeal” in support of the ICP, which he called a “party of the working class” that “will help the proletariat lead the revolution …”xvi Despite this, however, he emphasized the need for collaboration with other classes, the petty bourgeoisie, the intellectuals, even middle peasants and a section of the bourgeoisie. This put him at odds with the Comintern, for which he paid a high price and had to correct his “mistake”.

The radicals, taking advantage of the crisis of the early 1930s, immaturely pushed for a “revolutionary upsurge” among workers and peasants. In several rural areas “Red villages” were created. The French colonial regime’s response was so brutal that not only did they raze all these villages, but also killed and imprisoned thousands of communists, leading to the near annihilation of the ICP. This confirmed the misguided policies of the Comintern and the correct strategy of Ho and his supporters. After Japanese occupation, Ho, who had mysteriously disappeared form the political scene for almost 10 years, entered Vietnam in 1941. With Comintern’s changed policy emphasizing cross-class alliances, Ho created the Viet Minh, a broad coalition of nationalists, communists and different classes preparing guerilla warfare against the French and Japanese occupiers.

With the surrender of Japan, and before the Allied forces entered Vietnam, and aware of their negative attitudes towards a potential Communist takeover, the Viet Minh leadership cleverly decided on a general insurrection, leading to the 1945 revolution and seizure of power. They only had to fight for another seven years to defeat the French and over 20 years to defeat the Americans, before gaining independence.

As Tuong Vu notes, Viet Minh policies before 1945 were moderate, and even when they had gained power for a while in the north, they had announced that they had no intention of creating a workers-peasant state.xvii The radical faction, however, had always stressed workers’ leadership, particularly after 1951 and the establishment of the Vietnam Workers’ Party. All these calls for workers’ leadership were at a time when the Vietnamese working class was quantitatively and qualitatively very weak. Alexander Woodside points out that even 20 years later, in 1971, in the most industrialized cities of the North only 15 percent of party members were workers. Despite these facts, the radical faction under Truong Chinh succeeded for a while to convince the party that an immediate socialist revolution was possible.

As a whole, in all these cases, despite the active presence and sacrifices of workers and peasants during and following these revolutions, “working class leadership” remained solely a slogan and never materialized either during the revolution or in the post-revolutionary period; the working class was never transformed into the “dominant class”. These revolutions, undertaken in the name and in the interest of the working class, were led predominantly by communist revolutionaries comprised of the new middle classes and intellectuals. By overemphasizing the role of the working class, the revolutionaries alienated other social classes whose skills and knowledge were necessary in the process of transition from capitalism.

Economic System and the Socialization of the Means of Production

In all revolutions that communists succeeded in gaining and maintaining political power, a most complicated issue related to the overall economic and industrial policy was the question of public ownership of the means of production, a most significant pillar of socialist economics.

In Russia, this policy went through constant transformations and changes. April Theses had also called for the “confiscation of all landed estates”, “nationalization of all lands in the country”, and the “immediate union of all banks in the country in a single national bank, and the institution of control over it by the Soviet of Workers’ Deputies”.

The early land and factory confiscations, massive nationalizations and collectivization was followed by the War Communism of 1918-21, and then by the New Economic Policy (NEP) which until 1928 tried to modify some of the excesses of earlier policies. A mix of state- and market-controlled policies were put into effect. Lenin rightly had come to the conclusion that in order to prepare for the establishment of a socialist economy, this stage should continue for a long time. However, with the consolidation of Stalin’s power, the policies drastically changed again, pushing for radical forcible collectivization and the Five Year National plans.

Another major economic policy question related to the financing of rapid industrialization with emphasis on heavy industries. Since it could not be financed from within the industry sector, or foreign sources, it had to be extracted from the agricultural sector through differential pricing in favour of industry sector. This “primitive socialist accumulation”, as coined by the Bolshevik chief economist Preobrazhensky – and opposed by Bukharin – had a negative effect on agricultural production and peasantry, and was one of the reasons for the failure of NEP. Later, both Preobrazhensky and Bukharin were among the long list of prominent Bolsheviks who were executed.

Rapid industrialization and national development, no doubt, turned the Soviet Union into a most powerful country that defeated Fascism, and became a world superpower. The Soviet Union enormously contributed to many national liberation and anti-colonial movements, and its mere presence in the global scene helped many labour movements in the advanced capitalist countries. However, the system that was established did not and could not have the features of a true socialist system that would be able to sustain itself, and with enormous costs to the Russian working class, peasantry, intellectuals, and citizens in general, after seven decades eventually collapsed as a result of its internal contradictions and external capitalist and imperialist pressures.

In Germany, although with the defeat of their revolution, the communists did not get the chance to gain power and implement their economic policies, different socialist factions had their differences. During the short-lived cooperation in the Council of People’s Commissars in the aftermath of the first revolution in 1918, the left wing of the Independent Social Democrats and the Spartakists/Communists emphasized on massive confiscations and nationalizations, whereas the other faction of the Independent Social Democrats, and the Social Democratic Party were against such policies at that stage.

In China, Mao’s vision of the economy at earlier stages was still moderate. While large banks, industrial and commercial enterprises were to be owned by the state, Mao emphasized that “the republic will neither confiscate capitalist private property in general nor forbid the development of such capitalist production…”. On the issue of land, while the lands of the landlords were to be confiscated, “socialist agriculture would not be established at that stage…”.xviii

Many of these ideas were put into practice during the two rounds of the civil war against the Kuomintang, and the Japanese occupation, and were modified accordingly. In Jiangxi, where Mao established Soviets (1931-34), he followed a different policy which included massive confiscations, which led to the serious decline of agricultural and food productions, and pushed many of the rich peasants towards supporting the Kuomintang. Failures of Jiangxi period led Mao to modify the ultra-radical policy, and during the Long March and in Yan’an (1936-48) followed a more moderate land reform.

After coming to power, the land reform was implemented in three stages. Although lands of big landowners and some rich peasants were distributed, they were allowed to keep part of their land. Later, “lower-level cooperatives” were established, and at a higher stage the “higher-level cooperatives” or the so-called “fully socialist” coops were established.

With closer ties with the Soviet Union, the Soviet-type First Five Year Plan with emphasis on heavy industries and massive proletarianization was followed. Industries which were predominantly in the cities led to rapid urbanization, but had a negative effect on rural areas and agricultural production. Expansion of state and party bureaucracies also led to the rapid growth of the new middle classes and their expectations. To correct the “mistakes” of the First Plan, and the estrangement of the relations with the Soviet Union, Mao launched different campaigns including the Hundred Flowers Campaign (1956), and the Great Leap Forward (1958-62). The failures of these campaigns weakened Mao’s position, and led him to retreat.

The implementation of national plans continued, and the country went through drastic changes. From Socialist Education Movement (1963) to the Cultural Revolution (1966-76), all the achievements also bore great costs. With Mao’s death many of his policies were revised and with the persistence of serious economic problems, as of the Fifth National Plan, and particularly starting in the 1980s, the policy shifted towards “modernization, productivity, efficiency”, and more and more introduction of market economics, a process labeled as “socialist market economy” or “Socialism with Chinese Characteristics”. The policy included de-collectivization of agriculture, encouraging private and foreign investment, and later included partial privatization of state enterprises, and trade liberalization, a policy that, as Daler Jabaroff aptly suggested to be better called “capitalism with Chinese characteristics.xix

In Vietnam, as in other cases, one of the main issues was public ownership and nationalizations, and the policy kept on shifting. In the post-August revolutionary period, the constitution guaranteed private property for all citizens. In the post-French period, private ownership of national capitalists was recognized, and in the post-American period, the new constitution declared that land ownership belonged to the people and the state would administer it. After liberalization policies, the “right” of land use could be bought or sold. Collectivization also went through different phases before allowing peasants to use five percent of the collective land for private farming. In 1950’s, however, the radicals under Truong Chinh, followed extremely radical policies of land confiscations, executions and purges, leading to serious economic and social problems which ended in his removal from the position.

After 1975, a most complicated issue was unification and how to deal with the South. At first, despite pressures from the ultra-left who demanded immediate nationalizations, the newly formed Communist Party of Vietnam (merger of the [North] Vietnam Workers Party – renamed ICP – and the People’s Revolutionary Party of South Vietnam) acted very cautiously to prevent capital flight and brain drain. They put forward the policy of “walking on two feet” (socialism in the North and Capitalism in the South). But under pressure of the ultra-left, in 1977 the party decided to make the south “socialist”, moving towards abolition of private property in the cities and socialization of production in rural areas. Anticipating the reactions of the capitalist and the middle classes, “youth squads” were organized and were sent to thousands of enterprises the night before the announcement. The reactions were swift, leading to the flight of thousands of Vietnamese. The ensuing economic crisis, shortages of agricultural and manufacturing products, and black markets led the party to modify the policy and accept its “mistakes” in 1979. Some Vietnam analysts compared this shift of policy to the Soviet’s NEP.

In 1986, the party congress decided to replace the centrally-planned economy and follow a policy they called “Socialist-oriented market economy”. In “walking on two feet”, the right foot seems to have taken longer strides than the left foot, and the South pushed the North to capitalist, rather than the North converting the South to Socialism.

In all these cases, in face of harsh realities and internal and external constraints, the early revolutionary economic and social policies needed to be constantly revised and modified, failing to achieve the intended goals of establishing a socialist system, and eventually, and to different degrees, shifted towards predominantly capitalist systems, albeit under different titles.

Most socialist revolutionary leaders discussed here were devoted visionaries with unshaken convictions about socialist ideals, social justice, equality and the elimination of exploitation. However, the experiences of these revolutions show that, reaching the goals of socialism are far more complex and lengthy a process than envisaged. These cases point to the fact that establishing a post-capitalist/socialist system needs a set of objective and subjective pre-conditions that to different degrees were absent in the revolutionary process of these countries.

Lessons for Transition from Capitalism

As discussed elsewherexx, learning from the past experiences of both revolutionary and reformist strategies, a post-capitalist society is only possible when in the Gramscian sense, a counter-hegemony at different national and global levels is established to replace capitalism with a superior socio-economic system. The long and protracted process of transition to socialism involves a preparatory and transitional phase during the capitalist era, that in the absence of a better title can be called radical social democracy,xxi or democratic socialist orientation, to differentiate it from the failed “social democracies” that we have experienced so far, or “democratic socialism” that is not fully possible during the capitalist era, and is actually the aim of transition. It involves new forms of mobilization, education, organization and action. The new strategies, aiming at a clear and workable goal, will meld aspects of militancy of the revolutionary approach with the pragmatism of incremental reform, towards establishing democratic socialism.

This process requires a clear conception of the characteristics of the so-called first phase of post-capitalist society, the modes of transition and agents of transition:

The desired socialism, while maintaining the grand Marxian ideals, should be practicable, attainable or “feasible” as Alec Nove suggested many years ago.xxii The left in many cases has tended to disregard what is achievable under a specific condition. Many advocate the immediate establishment of socialism through revolutionary means, without considering how and with whose support they can achieve such end. This is particularly questionable in the advanced capitalist societies where the prospect of a socialist revolution is extremely remote at the present time, not to mention that such radicalism is relatively safe for the radicals, unlike what is experienced by their counterparts in authoritarian countries.

The democratic character of the socialist project is of crucial importance for its success. The past socialist revolutions’ disregard for the principles of democracy has been the most intense subject of criticism. Aside from the earlier criticisms of the Bolshevik Revolution posed by Luxemburg, Bernstein, and Kautsky and others, many contemporary theorists have also dealt with the subject, and have come up with different democratic models; from C. P. Macpherson’s efforts to bridge aspects of liberalism with socialism,xxiii Ernesto Laclau and Chantal Mouffe’s “radical democracy” based on ‘difference’ and not ‘consensus’xxiv, and Barry Hindess and Paul Hirst’s “associative democracy” based on ‘associationalism’xxv, to Norberto Bobbio’s “consensus democracy”xxvi, and others advocating “deliberative democracy”, based on ‘deliberation’ either by the representative bodies or by the ordinary citizens. Not to mention those who solely advocate direct democracy, council democracy, and non-hierarchical organizations, etc. While all these structuralist, post-structuralist, post-Marxist, post- modernist Marxists, and anarchists have contributed in different ways to the discussion of democracy, my emphasis here is on the reformed representative parliamentary democracy, in the manner Marx envisioned in his mature years. In response to the “revolutionary phrase-mongering” of the leaders of the Parti Ouvrier of France, he emphasized on the electoral process and the need to “transform … the instrument of deception … into an instrument of emancipation”.xxvii What is significant in relation to the question of democracy is that the majority should embrace socialist ideas and elect a socialist state. A reading of Gramsci also rightly points to this conclusion.

Furthermore, the desired socialism should be able to progressively optimize the quadripartite aspects of national development; economic growth, social equity, environmental balance, and political democracy. It requires a democratic, secular and participative state, which along with participative workers and employees’ councils, neighborhood, local and regional councils, develops its vision and policies, and implement them. Also, we need to remind ourselves that no full-fledged socialism is possible in one country, and that it needs a global context.

In terms of modes of transition, the desired socialism while peaceful and gradualist, should be optimally radical, and may even have to resort to “defensive violence” if needed. The experiences of past revolutionary and reformist movements show that when they are not radical enough they invariably lose, or have to concede, to reactionary forces. On the other hand, radicalism above the optimum level leads to adventurism which in a different way impedes progress towards the goals of social transformation. This does not mean that progressive forces should try to prevent radical actions taken by the workers or peasants, but that they should be thoughtful about the eventual outcomes. This is of particular importance now, when the reactionary populist and religious fundamentalist forces can take advantage of political crises or the immediate collapse of a political system to mobilize the masses with disastrous consequences. What we experienced in Iran is a most vivid tragic case of such a situation. Unaware of the probable consequences, we celebrated any seemingly radical move, including the disastrous takeover of the American Embassy in Tehran by the Islamist students, an event that was a turning point in the consolidation of power by the Khomeinists.

As for the agents of transition, unlike the emphases of the past since Marx himself, the working class with all its transformations, cannot be considered as the sole agent of socialism. On this issue also we have diverse perspectives ranging from those who continue to see the working class as the only capable agent of socialist transformation, to those who completely deny such a role. Gavin Kitching, for example, considered “mental labourers” as the main constituency of socialism and not the “traditional” working class with their mere material concerns,xxviii while Ellen Meiksins Wood, defending the traditional role of the working class calling him and all those who question working class capabilities as “Platonic Marxists”.xxixAndre Gorz’s emphasizes on the changes in the role of work, referring to the category of “non-class of non-workersxxx, while Michael Hardt and Toni Negri’s considered “multitude” as agent of global transformationxxxi. It is contended here, that while the working class which is the main object of exploitation, remains as a major agent of social transformation, the new middle class have a most significant role to play as do the so-called “identitarian” groups (feminists, anti-racists, national and religious minorities, …), a section of small and medium capitalists, and the “underclass”.

The overall political action model for the preparatory phase of transition to post-capitalist society includes a set of interrelated actions in different domains, involving different agents. This can be envisaged in a tri-dimensional matrix correlating “socio-cultural”, “political”, “economic” and “ecological” domains, with actions that include “education”, “organization” and “deployment”, and with agents that include the working class, the middle class, sections of small and medium capitalists and the identitarian groups.

Actions and activities related to these domains, while concurrent throughout the process, are at times sequential. Education and organization will be linked directly to the day-to-day problems of the working people and other agents, dealing with economic problems, political freedoms, liberties, and other issues people in general are confronted with. In broad categories, the focus on the cultural domain deals with creating a counter-cultural hegemony. With the “conscious” support of the “immense majority”, the political actions aim at taking political power through democratic means and direct action. Reforming and democratizing public and private institutions, and the introduction of participatory management at all levels of decision-making is an integral part of changes in the political domain, and subsequently changes in economic, social and environmental policies. Radical political party(ies) would play a most significant role in social mobilizations.

Economic transformation combines aspects of socialist strategic vision-building and regulated capitalist market-economy with the progressive dominance of the former over the latter. The extent of these reforms is obviously linked not only to the subjective and objective conditions at the national level, but also to the global situation and the progress of social-political movements in other countries towards socialism. As mentioned earlier, socialism in one country is not possible, as it needs a global context.

This is no doubt a most complicated and protracted process, but as compared to the revolutionary and reformist strategies of the past, has a better chance of moving towards the establishment of democratic socialism. Those socialist theorists, activists and political organizations that question the need for the preparatory phase of transition during the capitalist era, and continue to advocate for an immediate proletarian socialist revolution, need to explicitly explain their notion of the post-capitalist socialist society, and how different or similar they are or are not with the previous experiences of socialism. Furthermore, they need to clarify what exactly constitutes the working class, what is meant by its leadership role, and which other social forces, if any, do they consider as revolutionary subjects with whose help they wish to establish a socialist system. And finally, with what means and how exactly they intend to achieve their goal in a single country in today’s globalized economy.

1 Saeed Rahnema is an award-winning retired professor of political science and public policy at York University, Canada. He was the founding director of York’s School of Public Policy and Administration, and a Director of the Middle Economic Association. During the Iranian Revolution of 1979 he was a leading activist in the Left and Workers Council movements. His recent works in English include, The Transition from Capitalism: Marxist Perspectives, (2016), Palgrave MacMillan; “Neo-liberal Imperialism; The Latest Stage of Capitalism”, in New Politics, Vol. XI, No. 2, Spring 2017; and “Radical Social Democracy; A Phase of Transition to Democratic Socialism’, in R. Westra, Robert Albriton and Seongjin Jeong, Alternative Economic Systems: Practical Utopias in the age of Global Crisis and Austerity, Routledge, 2017.

i This article is the revised version of papers presented in the International Symposium on History, Reality and Future of Socialism in Beijing October 2017, and the International conference on Revolution: Historical and Philosophical Comprehension, Moscow, November 2017, commemorating the centennial of the Russian October Revolution. It is based on a book by the author; Saeed Rahnema (2018) Baz-khani Enghelab-haye Gharn Bistom (Revisiting the 20th Century Revolutions), Aghah Publishers, Tehran. The author would like to thank the reviewers of Socialism and Democracy for their comments.

ii Paraphrasing Allain Badiou, 2010, The Communist Hypothesis, Verso, London,. pp. 17, 21.

iii Marx, K. and Friedrich Engels, 1998, “Communist Manifesto,” in Socialist Register 1998: The Communist

Manifesto Now, ed. Leo Panitch, Colin Leys, London: Merlin Press, p. 250..

iv Marx, 1988, “Contribution to the Critique of Hegel's Philosophy of Law,” in Karl Marx, Frederick Engels: Collected Works, vol. 3, Marx and Engels: 1843-1844. Translated by Jack Cohen, et.al. New York: International Publishers, p.184.

v Marx, K. 1983, Capital Vol. 1, Ch. 32, Moscow: Progress Publishers, p. 715.

vi Lenin, V. I. 1964, “The Task of the Proletariat in the Present Revolution” (April These), in Lenin’s Collected

Works, Vol. 24, pp. 19-26). Among other sources consulted for the section on Russian revolution, are:

Browder, R. P, and Kerensky, A. F. , 1961, The Russian Provisionary Government, Stanford University Press.

Carr, E. H. , 1979, The Russian Revolution from Lenin to Stalin, 1917-1929, Macmillan

Defronzo, James, , 2006, “The Russian Revolution of 1917”, in Defronzo, (ed.) Revolutionary Movements in World History,

vol. 3, Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO.

Katkov, George, , 1967, Russia 1917; The February Revolution, Harper and Row Publishers.

Reed, John, , 1919, Ten Days that Shook the World, International Publishers. (internet)

Rabinowitch, Alexander, , 1976, The Bolsheviks Come to Power, New York: W.W. Norton.

Suny, Ronald, G, 1983 “Toward a Social History of the October Revolution”, American Historical Review, 88, no 1.

Trotsky, Leon, The History of Russian Revolution, Vols. 1,2, and 3, Internet Archive.

vii Lenin, V.I., “Last Testament; Letters to the Congress”, in Lenin’s Collected Works, Vol. 36, pp 593-611.

viii Harrison, Thomas, 2017, “The Tragic Fate of Worker’s Russia”, in New Politics, vol xvi, No. 3, Summer.

ix The Call, , 2007, January 30, 1919, in Marxist Internet Archive.

x Luxemburg, Rosa, , 2004, “Our Program and the Political Situation”, in Dick Howard, Selected Political Writings of Rosa Luxemburg, 1971, Monthly Review Press, in Luxemburg Internet Archive.

xi Ryder, A. J., 1967 The German Revolution, of 1918; A Study of German Socialism in War and Revolt, Cambridge University Press, p. 196. Among other sources consulted for the section on German Revolution, are:

Broue, Pierre, 2006, The German Revolution: 1917-1923, Chicago, Haymarket Books.

Mishark, John W. 1967, The Road to Revolution; German Marxism and World War 1 – 1914-1919, Moira Books.

Morgan, David W., 1975 The Socialist Left and the German Revolution; History of the German Independent Social

Democratic Party, 1917-1922, Cornell University Press.

Nettl, John Peter (1966), Rosa Luxemburg, London Oxford University Press.

Pannekoek, Anton, 1918, “The German Revolution; First Stage’, in Workers’ Dreadnought, 24 May 1919.

Rosenberg, Arthur, 1936, A History of the German Republic, 1918-1930,

Weitz, Eric D. 1997, Creating German Communism, 1890-1990: From Popular Protests to Socialist State, Princeton

xii Mao Tse-tung, “ The Chinese Revolution and the Chinese Communist Party”, in (1975), Selected Works of Mao

Tse-Tung, vol. ii, Pergamon Press.

xiii Ibid.

xiv Mao Tse-Tung, 1949, “On the People’s Democratic Dictatorship”, Selected Works of Mao Tse-Tung, vol. iv.

Among other sources consulted for the section on the Chinese revolution, are:

Blecher, Marc, 1986, China, Politics, Economics, and Society, Pinter.

Communist Party of China, Party Reform Documents, 1924-44.

Defronzo, James, 2011, Revolutions and Revolutionary Movements, Westview Press.

Lubell, Pamela, 2002, The Chinese Communist Party and the Cultural revolution, Palgrave.

Schurmann, Franz, 1966, Ideology and Organization in Communist China, University of California Press.

Skocpol, Theda, 1976, States and Social Revolutions: A Comparison of France, Russia, and China, Cambridge.

Sweezy, Paul, 1972, The Transition to Socialism, Monthly Review Press.

Thaxton, Ralph, 1983, China Turned Rightside Up: Revolutionary Legitimacy in the Peasant World, Yale University.

xv Khanh, Huynh Kim, 1982, Vietnamese Communism; 1925-45, Cornell University Press, p. 64.

Among other sources consulted for the section of the Vietnamese Revolution, are:

Duan, Le, , 1970, The Vietnamese Revolution, Fundamental Problems, Essential Tasks, Hanoi.

Duiker, William, 1983, J., Vietnam; Nation in Revolution, Westview

Giap, Vo Nguyen, People’s War, People’s Army, Foreign Language Publishing House, Hanoi, 1961.

Karadjis, Michael, 2013, “Socialism and the Market: China and Vietnam Compared’, in International Journal of Socialist

Renewal, 20 March.

Marr, David G., 2013, Vietnam: State, War, and Revolution (1945-1946), University of California Press.

Woodside, Alexander B, Community and Revolution in Modern Vietnam, Houghton Miflin, 1976.

xvi Ho Chi Minh, 2003, “Appeal Made on the Occasion of the Founding of the Indochinese Communist Party”, in Selected

Writings of Ho Chi Minh (1920-1969), Ho Chi Minh Internet Archive (Marxists.org),.

xvii Vu, Tuong, 2014, “Triumphs or Tragedies: A New Perspective on the Vietnamese Revolution’, in Journal of Southeast

Asian Studies, June.

xviii Mao Tse-Tung, (1939), On New Democracy, in (1975),. Selected Works of Mao Tse-Tung, vol ii, Pergamon Press.

xix Daler Jabaroff, 2017, paper presented at the International Symposium on History, Reality and Future of Socialism, Beijing, School of Marxism, Peking University, October.

xx Rahnema, Saeed, “Radical Social Democracy; A Phase of Transition to Democratic Socialism’, in R. Westra,

Robert Albriton and Seongjin Jeong, 2017, Alternative Economic Systems: Practical Utopias in the age of Global Crisis

and Austerity, Routledge, , and The Transition from Capitalism: Marxist Perspectives, (2016), Palgrave MacMillan.

xxi The term “radical social democracy” has been in use in different languages by different writers, and there are political organizations like Chile’s Partido Radical Socialdemocrata. My usage of the term, however, denotes a socialist-oriented movement during a capitalist era, and a preparatory phase for transition to post-capitalist society.

xxii Alec Nove, 1983, The Economics of Feasible Socialism, London: Routledge

xxiii C. P. Macpherson, 1976, “Humanist Democracy and Elusive Marxism”, Canadian Journal of Political Science, September ., cited in Leo Panitch, 2001, Renewing Socialism: Democracy, Strategy, and Imagination, ch.3, Westview.

xxiv Ernesto Laclau and Chantal Mouffe, 1985, Hegemony and Socialist Strategy: Towards a Radical Democratic Politics, Verso.

xxvBarry Hindess and Paul Hirst, 1977, Mode of Production and Social Formation: An Auto -Critique of Pre-capitalist Mode of Production, Palgrave; Paul Hirst, 1993, Associative Democracy, Polity.

xxvi Norberto Bobbio, 1979, Which Socialism?, University of Minnesota Press.

xxvii Karl Marx, 1880, “The Programme of the Parti Ouvrier”, Marxist Internet Archive.

xxviii Gavin Kitching, 1983, Rethinking Socialism, Theory for a Better practice, Law Book Co.

xxix Ellen Meiksins Wood, 1998, The retreat from Class” A New ‘True’ Socialism, Verso.

xxx Andre Gorz, 1982, Farewell to the Working Class: An Essay in Post-Industrial Society, Pluto press.

xxxi Michael Hardt and Toni Negri, 2004, Multitude: War and Democracy in the Age of Empire, Penguin Press.