…the urban waterfront has become a new frontier of the city with opportunities for significant aesthetic, economic, social and environmental benefits; it is also the new battleground over conflict between public and private interest – Kim Dovey1

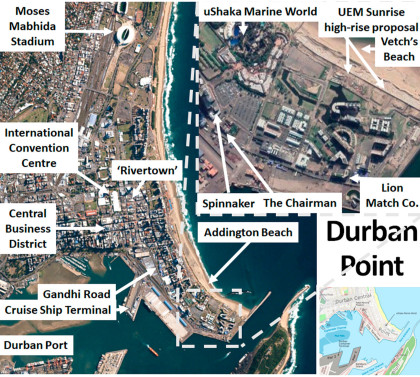

The Point Waterfront is one of the most stunning pieces of real estate in the city of Durban. Not more than two square miles in size, it is bounded on one side by the harbor and the Indian Ocean on the other. Protecting the area is the Bluff that lies on the south side of the harbor entrance. To the west rise the residential and then commercial buildings of central Durban. Along the coast to the north are Durban’s famous beaches – which when working well are South Africa’s most democratic spaces in terms of racial and class desegregation.

Today there are extremely high hopes for redeveloping this historic site, one spotted from the sea by Vasco da Gama when he sailed by in 1497, and subsequently once the sand bar was cleared, the entryway to the continent’s largest container port. One of the most famous scenes of white-on-white violence in South Africa unfolded here in 1842: the month-long siege of the Point’s Fort Victoria at the British Colony Port Natal (now Durban, also called eThekwini Metro) by what later came to be known as Afrikaners.

Figure 1. The Point Waterfront, Durban

Now, mayor Zandile Gumede predicts, redevelopment of “The Point Waterfront will completely change the landscape of Durban and position it as a global city and boost tourism profile. Cities are viewed as critical economic nodes and as stable to attract investment.”2

The revitalization process had begun about three years earlier, when Point property developer Herman Chalupsky claimed it would soon be “on par with Cape Town’s V&A Waterfront, the Docklands in London, New York’s Meatpacking District, San Francisco’s Pier 68 and other rejuvenated dockside areas across the world. We are very excited because this will be the most sought-after area in all of Durban.”3

In apartheid’s heyday of the 1960s and 70s, the Point was the site of smugglers and seamen who spent a few days on solid ground as the ships were prepared for a turn-around. On the bay side, the area was dominated by a yacht and surfing club, the preserve of Whites. Through the late 1980s, the area had become run down and all that remained were derelict houses: the majority of the land was owned by the parastatal agency Transnet mainly through its subsidiary Portnet, as well as the city of Durban. They allowed the place to literally gather dust. Then in the 1990s, the Point and the rest of the Central Business District (CBD) suffered from the flight of white business to the northern suburbs, especially Umhlanga, as the city center de-racialized. Moreover, mechanization of shipping meant Transnet shed thousands of jobs, so that once well-paid white artisans living in the vicinity of the Point drifted away. As occurred in many locations around the world, “The dockside cosmopolis that had once been an organic part of the working waterfront has faded into history, sunk beneath the waves of technological innovation,” observed Henry Trotter.4

Just as the African National Congress (ANC) ascended to power nationally in 1994 under Nelson Mandela’s leadership, there were strong hints that the Point would be re-developed, prompted by a major waterfront investment just before democratization. The area was given a boost as the new rulers in Durban City Hall confirmed they would continue supporting the uShaka Marine World theme park, water sports complex and associated tourist trappings.

The centerpiece is still a massive shark-filled aquarium, the world’s fifth largest, within a luxury restaurant designed to resemble wrecks of an old ship. Alongside are a watery playground alongside and the inevitable arcade of shops and restaurants. Durban taxpayers paid more than $60 million to subsidize the area: bait for property speculators to feed into and off. Named after the region’s first nation-building monarch, Shaka Zulu (1787-1828), uShaka opened on 30 April, 1994, three days after the first democratic election. The project has never broken even since, and uShaka Marine World required bail-outs worth $35 million in its first 15 years alone. These funds were the catalyst for further Point development to the south, towards the harbor entrance. This compact but potentially lucrative piece of real estate was to become the concentrated focus for some of the city’s most notorious rascals.

A quarter-century later, undeterred by under-utilised residential and commercial occupancy in the area, media headlines have again identified plans to revitalize the Point. The latest is a $2.5 billion Malaysian-driven development including an extension of the beach-front promenade, skyscraper apartments, restaurants and shops. A new cruise ship terminal will periodically disgorge the world’s elites, anxious to shop and party in a Durban that once again will serve as Africa’s gateway. The marvels of globalization will again bless Durban… or so goes the theory.

Deglobalization damages trade-dependent Durban

The reality is less rosy, especially in the primary circuit of capital where South Africa now confronts the harsh reality of declining local fixed investment and Foreign Direct Investment (FDI), as well as global trade rates. South Africa is one of the world’s ‘deglobalization’ losers, as was its manufacturing base as globalization peaked, prior to 2008’s financial meltdown. The SA Reserve Bank in June 2018 bemoaned how “capital spending by both the private sector and general government decreased … hampered by the constrained fiscal space, policy uncertainty (in the mining sector in particular), and very weak civil construction confidence.”5

South Africa faces a generalized problem: global over-accumulation of capital within an oligopolistic local economy, witnessed for example in Chinese steel dumping in South Africa, which forced closure of the second-largest firm (owned by the Russian Roman Abramovich) and threatens the largest (owned by the Indian Lakshmi Mittal). As a result, the South African economy is falling more rapidly than most when it comes to attracting FDI. Indeed in 2017, the shrinkage was 41 percent, down to just $1.3 billion in new FDI, compared to $7.4 billion in South African FDI outflows. The trend of net negative FDI began in late 2013, and no amount of municipal-scale investment marketing could reverse that. Nevertheless, in November 2017, World Bank consultant George Bennett bragged of his work over prior months, developing FDI plans with Durban officials: “It’s a really precise strategy, it’s set in place, and now the Council has agreed to fund it generously for the next 3 to 5 years. The World Bank would also have high expectations.”6

Such expectations are unrealistic because notwithstanding the palace-coup replacement of Jacob Zuma with pro-business tycoon Cyril Ramaphosa as national president in February 2018, Durban remained[s?] an unlikely city for economic revival. It suffers extreme internecine violence within the ruling party, and more than 150 politically-related assassinations were recorded in the prior five years, most at the migrant labor hostels of South Durban. There is generalized decay and widespread municipal graft. Indeed in June 2018, mayor Gumede herself was faced with damning corruption allegations, as a leaked forensic study recorded how several million dollars’ worth of sanitation tenders were given to cronies because, politically, “Gumede owed them a token of gratitude in the form of contracts.”7 At the same time, investigators from the national Auditor General’s looking into municipal graft suffered such fear from death threats that they withdrew from the job, though the ANC’s response was to re-endorse Gumede’s rule.8

Yet just three weeks later, the unfazed mayor led a large delegation to Britain. The main stop was in Newcastle, an appropriate sister city, Gumede claimed, “because we are having similarities in weather and in politics and also in how we do things” (sic). To some bemused onlookers, Moses Tembe, the co-chair of the KwaZulu-Natal Growth Coalition,

asked the British audience, “Where is the biggest business opportunity in South Africa? I want to tell you it’s Durban.” Prominent British real estate speculator Katie Friedmann – whose property firm ‘Urban Lime’ had recently purchased a large portfolio of trendy Florida Road buildings and, raising rental rates dramatically, evicted numerous family businesses there – argued that for AirBnb returns on capital investment, “number one in the world is Durban.” Durban deputy city manager Philip Sithole claimed implausibly that he had stirred up $8 billion worth of investor interest during the trip.9

The investment-attraction trip was reminiscent of Durban’s many prior claims to urban entrepreneurial success.10 But not only has FDI been crashing, so too have other indicators of Durban’s standing. Given the port’s status as the African continent’s most active for container throughput, one terrifying indicator was the dramatic collapse of the Baltic Dry Index, the world’s main measure of shipping, from a level of 11,500 in 2008 to below 1,500 since 2014.11 Ironically the decline in world trade/GDP ratios was led by the Brazil–Russia– India–China–South Africa

group that once were considered the ‘building BRICS’ of 21st-century capitalism. Not only was South Africa hit hard – as trade fell from 72 percent of GDP in 2007 to 61 percent in 2016, compared to world decline over that period from 61 percent of GDP to 58 percent. All witnessed reduced trade much further than the global norm, and three spending parts of 2015–17 in recession: Brazil, Russia and South Africa.

The ‘centripetal’ economic strategy referred to within the BRICS was, in reality, cannibalistic-capitalist under conditions of Chinese-driven over-accumulation, as the steel industry illustrates. The rhetoric remained collaborative-competitive, for Xi Jinping insisted at the 2015 BRICS summit that they must “boost the centripetal (unifying) force of BRICS nations through cooperation in innovation and production capacity to boost competitiveness.”12 In 2013, when Durban hosted the bloc’s leadership summit, the BRICS claimed they would lift all African boats on a rising tide.13 Such rhetoric can be expected to continue under rising Chinese domination, for as Xi famously put it in a plenary talk at the World Economic Forum in early 2017, just before Donald Trump took power:

There was a time when China also had doubts about economic globalization, and was not sure whether it should join the WTO. But we came to the conclusion that integration into the global economy is a historical trend... Any attempt to cut off the flow of capital, technologies, products, industries and people between economies, and channel the waters in the ocean back into isolated lakes and creeks is simply not possible... We must remain committed to developing global free trade and investment, promote trade and investment liberalization... We will expand market access for foreign investors, build high-standard pilot free trade zones, strengthen protection of property rights, and level the playing field... China will keep its door wide open and not close it.14

Xi was simply fibbing, for during six months starting in mid-2015, Beijing imposed stringent exchange controls, stock market circuit breakers and financial regulations to prevent two Chinese stock market collapses from spreading (beyond the existing $5 trillion in losses). Moreover, within eighteen months of his Davos speech, Xi had authorized a set of trade restrictions on U.S. products in retaliation for Trump’s protectionist tariffs. Channeling toxic waters of excessively centrifugal globalization back into economic purification systems is indeed possible, and necessary, at a time when the world economy’s self-correction puts places like Durban’s Point onto any map of over-exposed real estate, financially and ecologically.

Secondary-circuit scandals

‘We have no right to seize the Sind. Yet we shall do so, and a very advantageous useful, humane, piece of rascality it will be’ – General Charles Napier15

The Point sits on a sandy flatland, and what was revealed in October 2017 when gale-force winds swept across the area should make any local or foreign investor shy away. The waves leapt up from the northwest – i.e., inside the harbor (an unusually fierce inland-sourced storm) – with such ferocity that a massive Mediterranean Shipping Company vessel capable of carrying 10,000 containers was pulled loose from its moorings and jammed itself across the port entrance, requiring five tugboats to return to a safe space. In the turmoil of chaotic global flows – of trade, finance and weather systems – there are few places more exposed than the Durban Point.

This is especially true when it comes to real estate capital, developers, speculators and the kinds of political fixers who emerged in post-apartheid South Africa. It was in part due to desegregation and white residential flight that the Point became the accumulation playground for a number of scoundrels, including new ‘black economic empowerment’ (BEE) figures conjoined with foreign investors and local white capital. They all sought to turn profits through speculation in the secondary circuit of capital, which, as Henri Lefebvre remarked, at its best runs “parallel to that of industrial production”16 but at its most chaotic devolves into accelerated get-rich schemes.

According to the Reserve Bank, South Africa’s secondary circuit has, like manufacturing and mining in the primary circuit, witnessed national decline. For example, “The construction sector has made no contribution to overall economic growth since the first quarter of 2015 due to persistent weak building and construction confidence and the absence of meaningful fixed capital investment.”17 Nevertheless, in downturns when investors still need outlets for over-accumulated capital, spatially-specific uneven development is often amplified, particularly in speculative sites subject to vigorous place-marketing tactics, like Durban’s Point, no matter the over-population of real estate rascals.

If rates of return in the primary sector decline, as was especially evident in South Africa once competitive gale-force winds hit factories during the globalization era, followed by the commodity price crash of 2015, then one reaction is acute inter-urban entrepreneurial battles for primacy.18 This is process occurs naturally when flows of capital shift from the primary to the secondary circuit following a ‘Kuznets Cycle’ every 15–25 years.19 The Point Waterfront received its first financial injection in the early 1990s at uShaka, and then suffered a long downturn. By 2015, the uneven temporality of the process was quite noticeable to Business Day, the most sophisticated periodical in the corporate media:

A decade ago Durban’s Point precinct was dominated by dilapidated buildings that were home to vagrants and criminals. It has been transformed into a property market paradise, with upgraded roads and waterways leading to upmarket apartment blocks, restaurants, hotels and offices. But in the past few years development stalled. The city and developers blame this lull on the 2008 global recession and SA’s slow economic growth that affected many sectors of the economy, including property and leisure investment. Now the Point precinct is poised for another wave of development, including new skyscrapers.20

As Neil Smith (1996) argued, a ‘rent gap’ of that sort typically must exist before a disinvested area becomes a prime site for redevelopment, and an area’s deindustrialization is usually an indication that in the next Kuznets Cycle, old buildings stand ready for emptying, renovation and neighborhood-wide revitalization. Indeed during the mid-1990s, as manufacturing output from the nearby sweatshops of South Durban was rapidly replaced with much cheaper imports, large swathes of empty spaces became open for either warehousing within the booming commercial circuit of capital (especially as Asian-sourced container traffic grew dramatically), or for landed capital to hoard, awaiting the sort of gentrification boom that paid off for so many other urban seaside or riverside property bonanzas, including Cape Town’s V&A Waterfront.

At the Point Waterfront, however, it was municipally-subsidised infrastructure. A provincially-owned bank funded dubious projects, e.g. the Point’s notorious “Dolphin Whispers” building. These taxpayer gifts to developers provided the most fertile ground, as Durban’s new army of politically connected “investors” took advantage of what Jamie Peck calls “the systematic dumping of risks, responsibility, debts and deficits.”21

In 1995, the media announced with much hoopla that the giant Malaysian property firm Renong Berhad had put in a tender to develop the Point area. Renong’s plan was to build a waterfront with a mix of business and residential properties resembling other international luxury waterfront developments from Brazil, Australia and France. Well aware of the changing dynamics in Mandela’s South Africa, Renong sought a local BEE partner. From August to October 1995, according to an affidavit by David Wilson, a Brit based in Kuala Lumpur who served as one of the firm’s chief officers, “Renong held discussions with Mzi Khumalo, the chairman of Point Waterfront Company,…the Minister of Public Works and the Director General of the Public Works Department[,]

at which Renong outlined its ideas on how Point Development could be implemented as an empowerment project.”22

Renong decided its empowerment partner would be Khumalo, a man imprisoned for twelve years on Robben Island for his anti-apartheid activism. He seemed the perfect partner, what with claims to top-level government approval. But as Wilson prepared to make a presentation to the Board of the Point Waterfront Company in November 1995, a local resident – Schabir Shaik, who ran the ANC-linked Nkobi Investments – also emerged as a prospective developer. In his affidavit, Wilson wrote that a day before the presentation, he received a call from Shaik informing him that he should meet:

When I arrived at the offices it became evident that the purpose of the meeting was to try to intimidate Renong… Shaik proposed that a joint presentation should be made with his consortium. I rejected this proposal… Renong went ahead with its presentation… and was, to my knowledge, the only bidder left in the picture.23

But Shaik would not go away, and the project could not get off the ground as negotiations dragged on. Renong chairman Halim Saad asked Wilson to resolve the dispute over the BEE partners, following Shaik’s visit to Saad in June 1996. Court records would show that in this meeting, Shaik used his trump card, one Jacob Zuma, who was at the time the KwaZulu-Natal province’s economic affairs minister. Zuma had written to Saad on 31 October 1996, according to Wilson, promising assistance in meditating any dispute. Saad instructed Wilson to arrange a meeting with Zuma through Shaik at the latter’s apartment.

Throughout the discussion, Mr Schabir Shaik would introduce the topics discussed, whereupon Mr Zuma would confirm and expand upon what Mr Shaik had said. He said he was not happy with the persons nominated to represent the empowerment interests in the Point Development, although he offered no explanation for this. He proposed Mr Schabir Shaik should be involved in the project… During the course of the discussion it became increasingly clear that Mr Jacob Zuma was acting as if Mr Schabir Shaik had some sort of hold over him. At one point Mr Jacob Zuma made mention of the support and assistance he had received from Mr Schabir Shaik. I gained the strong impression that this support and assistance was of a financial nature.24

According to Wilson, his response was

… that Renong had no wish to get involved in this selection of empowerment nominees since this was a matter for the Government of South Africa to decide… It was our intention to continue with our existing empowerment partner unless formally advised otherwise by the Government of South Africa. Such an instruction was not forthcoming… it was clear that Mr Schabir Shaik was not a suitable business partner and no further discussions were held with him after 1997.25

Shaik held that he never attended the said meeting. However, Judge Hillary Squires did not believe Shaik’s version.26 Shaik and Zuma were to famously move on to greater heights; the $5 billion arms deal that Mandela’s government had put together from 1996 to 1999. A

s court papers were to reveal, Zuma intervened to assist Shaik in this deal too. When the French arms company Thales expressed doubts about Shaik as an empowerment partner, Zuma was called in, assuring the firm that Shaik was the right man. In turn, Shaik solicited from Thales an annual bribe for Zuma of what was then nearly $100,000.

Shaik was eventually convicted of fraud and corruption and sentenced to fifteen years in prison. Controversially, he was quickly paroled after serving only 28 months due to an allegedly terminal illness, and periodically made the news in Durban, e.g. when engaged in fisticuff attacks on fellow golfers. While Squires found that Shaik and Zuma were joined at the hip in their corrupt enterprises, Zuma has been able, through a series of legal manoeuvres, to avoid his day in court until after he left the presidency.

Khumalo, rumoured to have been upset by Zuma’s snub in favour of Shaik, sought to take revenge later by throwing his allegiance behind Zuma’s enemies. Khumalo’s notoriety arose from the fact that he cashed in on early BEE deals by “buying shares in companies at discounted prices and then quickly selling them on, making both a personal fortune and a mockery of the concept of empowerment,” as Martin Plaut and Paul Holden reported.27 Khumalo’s Metallon Corporation was involved in a number of seemingly dodgy deals, and in 2003 he “…pulled off a breathtaking coup whereby he somehow got the [state-owned] Industrial Development Corporation to lend him money with which to acquire from them 10.7 million shares in Harmony Gold at a discount, shares that he immediately sold at a profit of R1 billion” ($80 million) as RW Johnson recorded.28

The Point is plagued by such charlatans, their scandals and their ghosts. Another was Prince Sifiso Zulu, a party-loving businessman who was convicted of culpable homicide in 2008 when he drove his BMWx5 into a taxi, killing two and injuring ten others. He was drunk at the time. He later tried to commit suicide by jumping off the second floor balcony of his Bastille flat in the Waterfront area while attempting to evade police. He served nine months of a three year sentence.

After years climbing the government ladder through his connections, in 2005, Zulu was appointed as head of the board of uShaka Marine World at the Point by municipal manager Michael Sutcliffe, himself a resident of a penthouse flat nearby and source of endless controversy.29 Zulu had long been used to scoring lucrative contracts; in 2003, he landed a $3 million contract for parking meters in central Durban; he hosted a fundraiser for Zuma at Zulu’s cocktail bar, the Beach Café; and was on “the council payroll, to the tune of $3000 a month as a ‘consultant on city events’.”30 When the provincial government’s Ithala Bank tried to collect $4 million owed by Zulu, he claimed bankruptcy. He died aged 43 in September 2015, after a brief illness.

Not only would BEE tycoons like Khumalo and political hustlers like Shaik and Zulu use the Waterfront as their playground. Point Road, which traverses the harbor side with easy off-ship access for weary sailors, was long regarded as Durban’s Red Light District. In 1999, Illovo Sugar’s chairperson Glyn Taylor, one of the biggest names in the industry and a classic white Natal Old Boy, died in a flat just off Point Road. As Melanie Peters, writing in the Independent on Saturday of 15 May 1999, put it, prostitute Thandi Molefe (not her real name) confirmed how Taylor wanted to watch her play with herself (for R50 – about $12 then) while he masturbated: “As he climaxed he held his chest and gasped for breath.” Soon after, Taylor was found on the linoleum floor of the third-floor sex worker’s apartment, followed by controversial Independent coverage of his fate.31 Five years later, Point Road was re-named Mahatma Gandhi Road, to largely negative reactions stretching deep into the Indian elite in both Durban and India. In Delhi, The Hindu headlined, “Mahatma’s name for a street of vice!” Complained The Times of India, “SA prostitution hub to be named after Gandhi.”32

As the City continued to invest in Point infrastructure, newly minted developers saw potential piles of cash and weighed in. A local consortium put in a bid for a loan from a provincial bank to develop a ten-floor building – Dolphin Whispers – with 56 luxury apartments in the heart of the precinct. The consortium had some heavy-hitting people on board, including former president Nelson Mandela’s granddaughter, Nandi Mandela, and five Durban businessmen: Henry Masinga, Vaughn Charles, Marcel Henry, Rajen Naidoo and Craig Simmer. The company managed to secure a loan from KwaZulu-Natal’s Ithala Development Finance Corporation for $8 million in 2005, despite the maximum loan amount being restricted to a maximum of $1 million. Prainder Civils were listed as one of Dolphin Whisper’s major shareholders, along with Harkrishen Hansraj, who was acting as an agent for Jay Singh, a developer who would later gain infamy when his cheaply-built shopping mall collapsed in Tongaat, killing two workers. As Dolphin Whispers literally teetered due to structural flaws, the company kicked Prainder Civils off the job for shoddy workmanship, as the building was deemed unsafe for habitation. Given the loan’s irregularities, Dolphin Whiskers was liquidated in 2008 when it failed to pay a construction firm brought in to fix the defective structure.

Yet throughout 2000s, the same gang of rascals were being awarded contracts all over the city and beyond. Singh, Hansraj, Naidoo and Cloete were all involved in the Remant Alton company which bought the city’s bus fleet for $7 million in 2003 and sold it back to the city for $40 million five years later. Vaughn Charles, Whispers’ quantity surveyor, was found to be linked to illegal tenders, fraud and numerous scandals across the city, including in Chatsworth and Crossmoor when the city of Durban awarded his company a contract to secure tenders for housing upgrades. Charles, it appears, crooked the process in favour of the Doctor Khumalo construction firm, which was unqualified to carry out the job. Likewise, engineer Craig Simmer was one of the contractors hired for the construction of the $390 million Moses Mabhida Stadium built for the 2010 World Cup, a few miles north of the Point Waterfront. The stadium suffered a $40 million cost overrun. 33

Recall David Harvey’s warning,

The freer interest-bearing capital is to roam

the land looking for future ground-rents to appropriate… the more open the land market is, the more recklessly can surplus money capital build pyramids of debt claims and seek to realise its excessive hopes through the pillaging and destruction of production on the land itself.34

Gentrification truncated

Recklessness is also apparent in the hyped marketing associated with Durban’s failed gentrification strategies. Near the International Convention Centre, a fake ‘Rivertown’ district was created in 2014 and in 2015 was the main reason the New York Times Travel section proclaimed Durban the seventh place on its list of 52 to visit that year.35 Rivertown’s main interest was surreal place-marketing strategies drawing on deracialized nostalgia such as the ‘Beerhall Vibe.’36 Likewise on Gandhi Road, just west of the upmarket flats catering to the nouveau riche, there is the ‘Mermaid District’ with its own nostalgic brand for potential hipsters and creatives (a tiny community in Durban, as Rivertown boosters learned to their regret):

Perched in strong contrast against the dilapidation and urban decay in the historic Point Precinct of Durban is an illustrious story of a world class bar – ‘The Chairman’ – and in the near future an authentic Bombay Restaurant which will famously be known as ‘The Persian Tea Room’. The objective of this development is to create a destination location with world- class retail nestled between creative spaces and double volume, old wood-floored offices in open plan spaces overlooking the Durban Harbour.37

The Chairman has indeed had plenty of money thrown at it, and includes a unique bar where lowlifes prowling the street outside are kept away by body-building bouncers, and where you can order Moet and Single Malt Whiskies at inflated prices. Deception doesn’t come cheap.

If you’ve got a few million to spare, you could grab a pad at the Point Waterfront Development, a warren of swanky, high-rise apartment blocks with names like the Sails and The Spinnaker38 where apartments can fetch up to $1 million, and restored Edwardian townhouses nestle aside peaceful canal walkways. Old warehouses are set to be converted, and the Lion Match Company has moved its headquarters here, having built “a five-storey, 5 000m² mixed-use development made up of a 2000m² distribution warehouse, corporate offices, retail space and covered parking.”39

This all sounds promising from the standpoint of secondary-circuit accumulation, but there is a disconnection here. The promised bars, restaurants and shops to service the flats have just not materialized. Upwardly-mobile consumers complain that they have to drive through derelict, drug-riddled streets of the city to buy food in upmarket neighbourhoods.

To the rescue came the municipality in 2017, reviving the hopes of UEM Sunrise (also known as Rocpoint, crafted out of assets from the former Renong). Once again, one of Malaysia’s biggest property companies advertised their grand designs to uplift the area: “a Cape Town-style waterfront at the entrance to Africa’s busiest port… five- and six-star hotels, a 33-storey skyscraper, residential apartments, office parks and shopping malls.”40

Some residents of the existing Malaysian-built complex are not happy, having been deceived into thinking that their bird’s-eye view of the ocean would remain as such, unimpeded. It appears not, as skyscrapers and hotels planned for the waterfront precinct will block their prime ocean view. Karin Solomon, a Point resident and a member of Save Our Sunshine Durban, says those ‘duped’ into investing in the Point are now crying foul because they are to be duped again. “Many people who are currently living in apartments at the Point, who have lost millions due to the investment they have made there, now stand to lose even more. Some are sitting with properties they cannot sell because of the proposed high-rise buildings very close to their apartments.”41

Ill winds and rising waters

The wind, the rascal, knocked at my door, and I said:

My love is come! / But oh, wind, what a knave thou art/ To make sport of me…

(“The Wind, the Rascal” – D. H. Lawrence)

The sea dissolves so much/and the moon makes away with so much/more than we know-/Once the moon comes/and the sea gets holds of us/cities dissolve like rock-salt/and sugar melts out of life/iron washes away like an old blood-stain/gold goes out into a green shadow/money makes even no sentiment/and only the heart/glitters in salty triumph/overall it has known, that has gone on now/into salty nothingness

(“The Sea, the Sea” – D. H. Lawrence42)

Scandals abound on-shore and off-shore, especially when corruption and nature take their toll on the exposed infrastructure. For example, Transnet’s Maritime School of Excellence has pride of place at the Point, but in September 2017, the school head and financial manager were suspended after allegations of mismanagement and inadequate training for students. The school had been established to provide training in the much needed maritime sector, but promises soon fell into the port’s murky waters. Students were “trained in freight handling and some were sent to a private supermarket in Pietermaritzburg, working as bakers, merchandisers, and cashiers – at Transnet’s expense.”43 In a final twist, the Maritime school was flooded by the mega-storm which swept through the Point in October 2017.

The Point’s ability to withstand ill winds and rising sea levels is not impressive, making the $2.5 billion redevelopment project far less tenable for investors and their insurers than the hype suggests. Transnet’s shortcomings included widespread corruption in its rebuilding of shipping infrastructure. In December 2012, the national minister responsible for Transnet, Malusi Gigaba, admitted there were “systemic failings” in an oil pipeline running from Durban to Johannesburg. It had been rerouted from rich white areas through South Durban. Gigaba admitted, “Transnet Capital Projects lacked sufficient capacity and depth of experience for the client overview of a megaproject of this complexity. There was an inadequate analysis of risks.” Moreover, “Transnet’s obligations on the project such as securing authorizations – Environmental Impact Assessments (EIAs), land acquisition for right of way, water and wetland permits – were not pursued with sufficient foresight and vigour.”44

Transnet’s $25 billion port-petrochemical complex expansion project begins at the Point, and includes a shift of container traffic on extremely large ships ten miles south to a new “dig out” harbor at the location of Durban’s former airport. Construction on the new port was meant to begin in 2016 but the world crisis has delayed it until at least 2032. But the existing harbor’s extention began badly in 2011 when seven Chinese cranes were ordered on the opposite side of the shore from the Point. They included $8 million in payoffs – by Swiss-based Liebherr and China’s Shanghai Zhenhua Heavy Industries – directed to the Gupta family, which at the time had enormous influence within Transnet through its agent Salim Essa.45

The existing berths also needed deep digging – by at least four meters – to cater for ‘Post-Panamax’ ships that carry more than the 5000 containers. (That was the maximum size ship to fit through the Panama Canal until 2015, when a $5.5 billion deepening changed that.) In 2007, Transnet dug the harbor entrance four meters deeper and 90 meters wider, but in turn extreme storms and freak waves can now blow in much more frequently with more velocity. Around five percent of climate change causality can be attributed to dirty bunker fuels used by the world’s ships. In July 2012, gale-forced winds bumped a ship up against the main cranes, doing weeks’ worth of damage.46

To carry out its EIA work on the next stage of port expansion, Transnet hired Nemai Consulting in Johannesburg, supported by climate denialist maritime experts who refused to acknowledge sea-level rise.47 Following years of correspondence with critics in South Durban,48 the national Department of Environment rejected the Nemai EIA in 2013, agreeing with activists that Transnet had not “applied its mind” regarding climate-related storms and rising sea levels, nor did Transnet’s proposed [?] consider the damage done through removal of a section of an ecologically vital sandbank next to the main berths.49

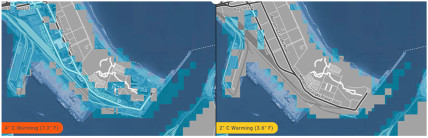

Rising sea levels will submerge waterfront buildings by 2100: two scenarios

Figure 2. Rising sea levels will submerge waterfront buildings by 2100: two scenarios.

Source: Climate Central Surging Seas monitor50

To help circumvent these kinds of delays, the national Economic Development Minister, Ebrahim Patel, pushed through a 2014 law to fast-track mega-project EIAs. When South Durban’s Goldman Prize winner Desmond D’Sa, the city’s most famous eco-social activist, travelled to Parliament that year to express concern, two ANC parliamentarians (Francois Beukman and Elsie Mmathulare Coleman) rudely shut him down just four minutes into his formal testimony.51

As if to prove the critics’ point, on October 9–10, 2017, gale force winds of up to 120km/hour and torrential rain wreaked havoc across the city and surrounding areas, with vehicles floating in rivers that once were roads and gaping holes in buildings where roofs and windows relinquished their hold. Across the municipality, eight people lost their lives. The hurricane left a huge financial and environmental headache in its wake. At the entrance to the harbor, photographers gathered to capture the unusual sight of a container vessel laden with cargo listing uneasily across the harbor mouth, blocking anything from entering or leaving the port.

During the storm, two 40-foot containers were dislodged from one of the ships, spilling 49 tons of plastic material into the port’s waters. It would prove to be an ecological nightmare for the South African coastline. The containers were on the Mediterranean Shipping Company’s MSC Susanna, and the cargo was packed with ‘nurdles’: plastic pellets which when melted were used to manufacture all manner of products. In the aftermath of the nurdle spillage, the city’s beaches were soon crawling with humans sifting through sand to filter out and dispose of the lentil-sized plastic pieces.

The cleaning operation has been on-going since October 2017, but as of March 2018, of the 49 tonnes which spilt in the water, only 12.38 tonnes were recovered, a quarter of the total.52 Wildlands Conservation Trust chief executive Andrew Venter estimated that nurdle removal would continue for the next two to three years and most would still not be recovered. Not only was there an impact on the marine life stretching hundreds of miles up and down the coast, the spillage adversely affected “the livelihood and health of 12000 subsistence fishermen in Durban.”53

Meanwhile, basic infrastructure investment and services are still missing for hundreds of thousands of residents in the South Durban Basin, especially affordably-priced housing, renewable energy, water, sanitation, clinics, day-care centres, other municipal services and public transport plus labour-intensive, green employment. But this kind of infrastructure is the polar opposite of the massive white-elephant, high-carbon, high-polluting, low-employment, corporate-welfare project envisaged by Transnet. In addition, climate change adaptation infrastructure to help the businesses and residents around the Point withstand extreme weather is also in short supply, as witnessed in the appalling problems with maintaining sand levels crucial for tourism on Durban’s main beaches.

Shifting sands

Capital is not a thing, but a social relation between persons, established by the instrumentality of things. – Karl Marx

Vetch’s Beach and pier stretch from the north side of the Point to the harbor entrance, and was once a thriving, bustling fisherman’s paradise, with one of the best views of Durban. It was popular with locals catching the fading light of day while feasting on local delicacies fried on the spot. Although for long a whites-only stretch of the sand, it subsequently desegregated and became one of the finest children’s beaches. Generations of young surfers learned to stand there, on placid but reliable waves, and scuba divers enjoyed a small coral reef within the protected waters.

Now, a security guard paces up and down the empty concrete path, warning trespassers off the pier. The south side of the harbor entrance is more open – though much harder to reach – because after a long battle led by D’Sa against the city, Transnet and even the U.S. government (which in 2004 had insisted that the entirety of the port be closed to fishing for anti-terrorist security purposes), subsistence fisherfolk were granted permission to return to the Bluff side of the pier.

Part of the reason offered for the delay in the widening of the harbor and extension of the brick promenade was a court wrangle between various long-established clubs in the area – Paddle-Ski, Undersea, Ski Boat, and Point Yacht – and the Duran Point Development Company. The latter succeeded in brushing aside the traditional beach users’ access rights. The Point Yacht Club was razed to the ground and boaters were accommodated in temporary buildings and marquees. The old boat sheds abutting Vetch’s were dismantled. The extension of Durban’s promenade is underway, establishing a walkway from Blue Lagoon to the harbor entrance. Deputy city manager Sithole proudly claimed:

It will extend the Golden Mile well beyond five miles from the Umgeni River to the harbor entrance, entrenching its appeal as probably the longest beachfront promenade in Africa. Durban will take its place alongside other major beach locations of the world, from Copacabana in Rio to South Beach in Miami and Bondi Beach in Australia.55

As Cape Town struggles with strict water restrictions due to drought, Durban’s share of tourism has benefited, with domestic and international visitors steadily rising in number. In April 2018, an agreement was signed between Transnet National Ports Authority and KwaZulu Cruise Terminals to commence the construction of a glittering new $15 million terminal in Durban’s harbor. Transnet announced “up to 10,000 employment opportunities generated through multiplier effect, of which over 100 will be direct jobs during the operation phase, and the future employment of interns in the maritime and cruise tourism sectors.”56 Other over-optimistic statistics were offered about the growing popularity of cruise holidays, as Transnet proclaimed how “the agreement was set to fundamentally change the current landscape, being an epitome of an Africa that was rising and a marine economy that was re-inventing itself.”57

In reality Africa is sinking, for rising sea levels will continue to cause havoc along Durban’s coastline, especially at the Point. The fickle cruise liners may begin to favor Durban as a port of call for international tourists, but that in turn depends upon further gentrification of the Point.

Figure 3. UEM Sunrise high-rise proposal.

While all these accolades and possibilities mount up, digging has commenced and the Point Development Company released images on their website of shiny, skyscrapers, reminiscent of a Dubai skyline. The website extols the ever forthcoming virtues:

The Point Waterfront will rapidly become the focus of the country’s cosmopolitan crowd, attracted by its fun, vibrant and easy atmosphere. It is here where the golden beaches are wide and welcoming. Flotillas of watercraft lie idling on the beaches, waiting to be launched into the Indian Ocean…This is to become the unrivalled, elite cosmopolitan playground for the people of Durban and its visitors, whether they are local or foreign…This is where the world will come to play.

Wandering through the area in 2018, however, one gets the sense of a distinctly[?] run-down zone. Many of the apartments lie empty as people who initially bought flats struggle to pay the upmarket levies for a neighborhood with no amenities. The rich of Durban prefer gated estates up the North Coast where they don’t have to run the gauntlet of Mahatma Gandhi Road, populated mainly by African migrants who throng the pavement at night.

City elites make no attempt to try and homogenize diversity; instead, they demonize. Point property developer Herman Chalupsky justified the beachfront promenade’s extremely slow development following the 2010 destruction of working-class restaurants during the World Cup 2010 renovations: “They want to attract the best clientele for the area. Whatever businesses go there need to enhance the promenade. We will source potential clients and scrutinise the tenders to get the best possible people in. The delay is simply to make sure the right calibre of people is operating from those outlets.”59

Tellingly, just a day after the local newspaper trumpeted that Durban was the country’s most liveable city in 2018, it was revealed that the city was expelling what it defined as vagrants, a practice begun at the Point’s residences by Sutcliffe more than a decade earlier.60 Fred Peter of the Beaumont Eston Farmers’ Association told a local newspaper:

When [Durban municipality] does a clean-up they load up their undesirables from the CBD and Albert Park, take them in the back of prisoner transport trucks and dump them in rural areas. They could have died from hypothermia. It is criminal. They are making it someone else’s problem

.61

‘…an architecture of spectacle’62

Speculation is both the lifeblood of the city and the mechanism that drains it of vitality, the instigator of greed that turns men and women into vampires and plunges them into debt – Sharon Zukin63

Despite the decaying feeling, parts of the waterfront do present a beguiling, idyllic setting. The Masterplan of Durban Point Development Company articulates a vision of:

A world-class development, that integrates a mosaic of influences of what is good and what is the best from the renowned playgrounds of the world. The masterminds behind this project offer up a highly crafted approach whereby energy, vigour and dynamism are the basic elements which comprise the foundation for this concept. It is all about creating opulent living within magnificent surrounds. Luxury lifestyle living that has never been experienced on this scale before.

What is good and what is best for Durban tourism and locals have not consistently been on the minds of municipality officials, however, as recent pictures of Durban’s rapidly eroding beaches lay testament to. There is trouble in paradise. Problems abound, encapsulated in “two worlds colliding at the shoreline – the beautiful, flexible and infinitely adaptable world that is a beach, and the static, inflexible, urban beachfront world.”64 In Durban, this is manifested in a city that is rapidly losing its famous central beaches.

Incompetent planning and Transnet’s disregard for the harbor widening’s impact on sand distribution, compounded by the effects of climate change, have resulted in a seaside city without sandy beaches. Where will people play in this ‘renowned playground’? According to the leading environmental journalist, Tony Carnie,

The major root of the current problem can be traced to 2007‚ when the old north and south piers were demolished during a $350 million harbor-widening project. Since then‚ the city has been limping along with a “temporary” and apparently dysfunctional sand-pumping scheme‚ because Transnet had to demolish the main sand pumping station and now – more than a decade later – has yet to commission a new sand hopper storage centre to properly replenish Durban’s eroding beaches.65

Like the tides which sweep in and out of Durban, there is no accountability for the fact that the bulldozers and recent shifting of sands on the beach itself have destroyed all marine life on the reef and along the Golden Mile. Remarked municipal spokesman Thozi Mthethwa,

This is a result of the effects of climate change‚ coupled with over-mining of sand. To mitigate the situation‚ the Municipality has employed several strategies. These include ensuring that beach sand washed out by the currents is swept back by municipal employees.66

This is as futile as Xerxes ordering the seas to be whipped; as King Canute holding back the waves. The issue has been compounded by the construction of piers resulting in a disruption of the natural drift of sand across the bay. Pilkey and Cooper tell us that dunes and wide beaches protect buildings from storms far better than sea walls:

The beach is a wonderful, free natural defence against the forces of the ocean. Beaches absorb the power of the ocean waves reducing them to a gentle swash that laps on the shoreline. Storms do not destroy beaches. They change their shape and location, moving sand around to maximise the absorption of wave energy and then recover in the days, months and years to follow.67

In Durban, artificially replenished beaches mean that tons of sand need to be dredged and dumped, causing severe damage not only to natural wave action, but also to marine life. These pumped-up beaches also erode much quicker than natural beaches, Pilkey and Cooper point out:

As time goes on and as the sea level rises, the interval of re-replenishment will get shorter because the beach becomes less stable. Beach replenishment is only a plaster that must be applied again and again at great cost. It doesn’t remove the problem, it treats the symptoms. Eventually and inevitably beach replenishment will stop either as sand or money runs out.68

As local environmental activist Desmond D’Sa predicted,

...no attempt to try to re-engineer the beaches would work in the long run. He said the city needed to shoulder the blame for the erosion as it had ignored various warnings from environmentalists and concerned citizens. “They got rid of all the vegetation and now there is nothing to hold the beaches together. Nature has its own course and no amount of concrete can stop it.”69

Meanwhile, the project’s main marketing website extols the virtues of a forthcoming ‘Sky Bridge’ that will provide a Point link with uShaka Retail, across which visitors can easily walk across without any traffic interference, thus blending the existing and proposed development as one: “This precinct will contain the following catalytic projects: a) A 54,600m2 signature five–six-star hotel of approximately 350 rooms. b) A 38,300m2 luxury condominium complex of approximately 360 units. c) A retail complex of 48,000m2 that will host daily food stores, fashion boutiques and branded outlets.”70

But today, a walk around the area is a ghostly experience – the neat canal houses are bereft of life, the promised shopfronts and restaurants are devoid of display or custom, the gondolas lap idly by the quayside, and small sharks grow inside a canal enclosure while sharks outside circle for a greater bite of waterfront riches. Many of the beautiful crumbling façades of Point Road are boarded up or lay in ruins, their innards picked clean by city residents.

Some signs of life spring up: the Ciao Bella restaurant; a smart atelier; printing and design studio. Propertuity, a company founded by Durban native Jonathan Liebmann specializing in urban renewal, has its sights set on the area with a development called Turning Point, with high expectations due to the well-publicized 2009–18 gentrification success story in Johannseburg’s Maboneng district.71 According to their website, their aim is to “re-ignite the concept of Durbanism, a culturally rich and urban Durban.”72

‘Durbanism’ was also Propertuity’s slogan for the failed Rivertown venture, launched with exceptional hype at a world architecture congress that Durban hosted in 2014. But everyone who lives or works in Durban knows that a rich culture has existed for generations. As expressed by Jane Jacobs: “There is no logic that can be superimposed on the city; people make it, and it is to them, not buildings, that we must fit our plans.”73 Located on the site of the old Cosmopolitan Action Bar, the newest Propertuity development is aimed at residential apartments whose “uniquely themed interiors acknowledge and reflect the values of urban South African society.” [Same citation as 73?]

One barrier to beachfront development – the legal wrangle between the Vetch’s boating clubs and the development company – did ultimately end with a controversial vote in late 2017, as the former moved out to make way for a planned extension of the promenade and residential and business development of the area. Point Yacht Club (PYC) manager Darryl Williams remarked, “The settlement will allow the PYC to continue conducting sailing regattas and activities from its own club at the Vetch’s Precinct, without reference to other parties and on terms which it finds extremely acceptable.”74 The elites always seem to be able to reach a compromise.

Creative strategies to take advantage of unique real estate continue on the Waterfront. There is a wedding venue called the Bond Shed. Bigger and better drawings of high-rise apartment blocks proliferate, plunging onto the promenade’s extension, as close to the shore-line as possible, climate change be damned. The fact that large parts of the city’s main beaches have literally disappeared is lost on city planners as they seek to deepen consumption spaces and tourist numbers. As Andy Merrifield points out, this is analogous “to inventing new niches for further rounds of dispossession and contagious proliferation.” Among these are “creative accountancy and creative ways to avoid paying tax; creative devices to gouge fees from ordinary citizens (especially in utility bills)… creative destruction of competition to garner inflated rents and profits; creative excuses to cadge money from the state. The list goes on creatively.”75

Perhaps it is fitting that the two original post-apartheid rascals of the Point, Jacob Zuma and Schabir Shaik, are back in the news, now that a new round of capital accumulation might begin. The National Prosecuting Authority revealed in March 2018 that it will reinstate charges against Zuma. Featuring no doubt in the case will be the machinations that went on while Zuma was MEC and Shaik his bagman, with both Shaik and David Wilson expected to give evidence in Zuma’s trial.76 How did William Faulkner put it: “The past is not dead. It is not even past.”

In fact, at the Point, the past keeps returning, often with the same actors dressed up with new titles. Mark Gottdiener’s notes how real estate speculation spawns bust-and-boom cycles of investment, and “propels the never ending process of property turnover and spatial restructuring whether an area needs it or not.”77 Yet the sod turning ceremony for the extended promenade was an occasion for Gumede to make startling claims at a time Durban desperately needs employment opportunities: 11,000 temporary jobs will be created and in the longer term 6,750 permanent jobs at the Point Waterfront:

Furthermore, we are also expecting that local existing property values in the area are likely to increase by at least 10 percent and the overall CBD property values by 5 percent. Upon completion, rates revenues generated will amount to in excess of $15 million more per annum… Overall national public revenues that may be derived from the revised development through the various tax mechanisms could amount to an additional $130 million.78

Gumede revealed that the City’s partners would be Malaysian investors UEM Sunrise – once a subsidiary of Renong – and local empowerment groups. So there we have it. History comes full circle. The same Malaysians are back. The local rascals are lining up at Ithala Bank whose headquarters is now conveniently located on the Point. Wild claims about property values and revenue extraction are bandied about. But so too does resistance rise.

Conclusion: top-down and bottom-competition over secondary-circuit capitalism

The architecture of spectacle is not a one-way, top-down process. There are many dissenters: those older or more recent dispossessed residents, those who work (including subsistence fishing), and those who play at the Point. They too have made their cases, even if they generally just plead for a small space of their own in this turbulent site of speculation, and often in a contradictory manner that highlights uncomfortable intersections of class, race and space.79

The post-apartheid era was increasingly tense in Durban and across the country, viewed from communities of poor and working-class people whose rate of social protest began rising not long after Mandela took power, just as did unemployment, poverty and inequality. But in 2004, a decade after political liberation, the catalyst for the first recorded post-apartheid protests at the Point was an incident that occurred far away, in New York City, on September 11, 2001. After the attack on the Twin Towers (and the Pentagon military headquarters near Washington, DC), the U.S. government began imposing extreme safety regulations on airports and ports, even as far away as Durban, starting in 2004. The authorities went even to the extent of banning subsistence fisherfolk from the Point Waterfront and other favored sites. Explained Daily News reporter Mpume Madlala, “The International Ship and Port Facility Security Code, developed in response to the perceived threats to ships and port facilities in the wake of the 9/11 attacks in the U.S., had been used to keep fishermen out.”80

“No Fish, No Living!”; “No Fish, No Rent!” These were the impassioned pleas from over 200 fishermen who gathered at Speakers’ Corner in Durban on 24 November 2004. They were protesting against the closure of the South Beach Pier. This was the first time that subsistence fishermen had organised against the war being waged against them… For many of the fishermen gathered there, the closure of this Pier is akin to a knife in the heart. Impassioned discussions were held as we marched together under the hot Durban sun…

Fishermen are seen and treated by local government in the same way that street children are: a nuisance, a hindrance to profit, an eyesore. Hence they are accorded the treatment equivalent of a pest. They are swept away, closed off, alienated, pushed to the periphery. Many of the fishermen at the protest were asking how they were supposed to survive if fishing was their only means of survival: what will happen to them if they cannot fish anymore?...

Des D’Sa and many of the fishermen from Kwazulu–Natal Subsistence Fishermen are adamant that they have had enough. Many feel they have been dealt a great blow. They suffered under apartheid and were denied access to beaches such as the North and South Beaches which are the best fishing spots on the coast only to suffer another forced removal—only this time it’s in a democracy, a democracy they feel they fought equally hard for. They are organising themselves and are resilient of the fact that they will not take this closure lying down. These are not fishermen who pull out a thousand fish a day. They take from the sea only that which they need to survive for the day: enough fish to sell at the local markets so they can put food on the table…

As their banners scream out at the injustices, and with tears rolling down their cheeks as they marched under the Durban sun, old and young together with the generations before them, they have made their first mark on Durban. The Fishermen revolt! A luta continua!81

It took nine years of organizing and protest, but the campaigners finally won access in 2013. Madlala continued, Spokesman for the Subsistence Fishers Forum, Desmond D’sa

… hailed it as a “major” victory to be finally recognised as port users after many protests and years of fighting to be allowed access… “The saddest thing was that people who had boats could happily fish around the harbour, but not us. We were treated like terrorists.” D’Sa said a lot of the fishermen had lost their jobs as the result of factories closing down years ago. “For them fishing is not just a hobby, but it is their livelihood. Our lawyers helped us through every step and we are very grateful.”82

The celebrations were premature, as the secondary circuit’s accumulation requirements took over from U.S. imperialism in 2015, resulting in the municipality and Transnet banning fishing again. As reported by Zainul Dawood,

The pier, at the entrance to the port and near the Point Waterfront, has been closed to the public since the harbour entrance was widened. This area and its surrounds have been earmarked for tourism development, including a world-class cruise ship terminal that would dovetail with planned development around the Durban Point Waterfront and tourist attractions such as uShaka Marine World. “We are sympathetic to the forum members’ perspectives, but need to balance this with the sustainable development of a port that will continue to serve the city and country to its full potential.” 83

That struggle continues, including in mid-2018 when the same fisherfolk marched at the Point against not only restrictions on fishing, but also on the exploration for oil and gas underway offshore Durban, by ExxonMobil, Statoil of Norway, Eni of Italy, and South Africa’s Sasol.

In a different way, traditional users of Vetch’s beach and boating facilities were partially defeated in their long struggle to defend their space. In 2013, the Durban Point Development Company (DPDC) – the fusion of the Malaysian developers and the municipality – finally wore down the two main associations still resisting: the Save Vetch’s Association and the Durban Paddleski Club. The warring parties “ceased hostilities,” as they put it in a statement, after DPDC made concessions. The latter, according to journalist Arthi Sanpath, had claimed that company plans would

close off the beach to the public, destroy the popular diving reef and leave many watersport enthusiasts without a venue. The compromise solution has been described as saving at least 200 meters of beach. But it allows the DPDC to go ahead with plans to build a super-basement – which will form the first phase of the project – and allows for a new ‘iconic’ hotel and waterfront development at the mouth of Durban Harbour.84

The main explanation of how assimilation proved acceptable to this network – whereas fisherfolk were completely denied access again and again – is the potential to continue a white’s-only racial segregation but now under DPDC’s private auspices. The water clubs had retained bad habits of de facto discrimination that attracted protest in January 2016. The catalyst was widespread anger at a real estate agent (in a small town south of Durban), as the Daily News reported:

Protesters claimed the club was practising racial segregation and vowed they would not allow the beach to be ‘privatised.’ The action was sparked by racial slurs made on social media by Penny Sparrow, who likened black beachgoers to ‘monkeys.’ One of the protest organisers, Nkosi Zuma, put pictures on his Facebook page with the post: “They won’t privatise our beach and call us monkeys at the same time. We invaded their private, whites-only club to put a stop to their racial segregation. We just wanted to buy water.”

By yesterday the post had been shared more than 1400 times and had sparked a debate about the club’s membership criteria and demographics. Zuma and a few others had invited social media users for a swim at Vetch’s Beach on Tuesday and photographs on his page of the protest included people eating bananas in an apparent reference to the Sparrow furore.85

The experience related by journalist Paddy Harper (who is white) and a black colleague a few days later is instructive:

A sea of hostile white faces stare at us as we pass the first of several Members Only signs on the Point Yacht Club’s precast wall and make our way through an outside dining area dotted with tables and umbrellas towards the restaurant and bar it shares with the Durban Undersea Club. There’s not a single black person seated at the tables behind the wall, the scene of protests earlier this week.86

But the Point’s racism is not only white-on-white: residents who are darker-skinned immigrants from the rest of the continent also suffered immensely in recent years. The Point’s northern end contains a few dozen of the CBD’s hundreds of mid-rise blocks of residential flats, some of which splay into the Addington Beach area immediately adjacent to uShaka. Mostly of 1940s middle-class vintage, they have been allowed to deteriorate, some to the point of no return. These are the post-2000 homes of countless immigrants, some of whom who are formal refugees due to their tragic histories in war-torn zones of Africa, as well as those of [?] many more economic migrants.

Their status is perpetually renegotiated, especially Zimbabweans resident in South Africa who face erratic changes in Home Affairs residency regulations.

Not far away, xenophobic tendencies ebb and flow within the beleaguered working class.87 On 16 April 2015, a few hundred immigrant activists attempted to march on City Hall against the wave of xenophobic attacks that began the previous month in South Durban’s Isipingo main street, after the Zulu king Zwelithini had compared immigrants to “lice” which needed to be killed. Attacks on Congolese small-scale merchants began there, quickly spreading to the low-income townships. Soon the xenophobia threatened inner-city immigrant residents. When the activists gathered to demand state protection, police sprayed purple-staining water on them and prohibited a march up the main street, Pixley ka Seme, although a small rally was permitted.

A few days later, xenophobes burst out from public transit area and beat up immigrant sidewalk hawkers. The following week, in a well-publicized march of several thousand mainly South Africans called by the ANC leadership to douse the xenophobic flames, a pro-xenophobia rump at the back got loose and confronted Congolese, Nigerian, Zimbabwean and Malawian immigrants. But there they met their match. The immigrants threatened “urban guerrilla warfare,” and this was not idle, as many hailed from amongst the continent’s most conflictual sites: the Great Lakes region where millions have died due to the resource curse, and the oil-rich Niger Delta. The immigrants pushed back local attackers, making this dilapidated section of the city their fortress – not good advertising for the nearby attempt at gentrification at Liebmann’s Rivertown, especially Pixley House which directly overlooked the battle.88

In spite of this widespread social chaos and conflict, the secondary circuit of capital continues to reshape the Point. A study by international group Mercer in 2018 on “Quality of Living” around the world found that Durban is South Africa’s most liveable city,89 and in that spirit, to attract yet more foreign tourists and expatriate workers, Durban must look like other exotic locations. This is part of the overall drive to turn Durban into what Harvey labelled the entrepreneurial city, in which “the public sector takes the risk and the private sector takes the benefit”90

thanks to “the speculative construction of place rather than the amelioration of conditions within a particular territory.” To return to Lefebvre’s point on the secondary circuit of capital, Merrifield warns,

Profitable locations get pillaged as the secondary circuit flows becomes torrential, just as other sectors and places are asphyxiated through disinvestment. Willy-nilly people are forced to follow hot money, flow from the countryside into the city, from factories into services, from stability into fragility. The urban fabric wavers between devaluation and revaluation, crisis and speculative binge, a ravaged built form and a renewed built form – and a fresh basis for capital accumulation. Once, it was a gritty warehouse or a rusty wharf; now, it’s a glitzy loft or a prim promenade. Once, it was an empty field on the edge; now it’s core neighbourhood on the up.91

As developments in the Point illustrate, hot money ebbs and flows, but so does nature and society – not always in sync. One danger of affording so much social respect to the huckster mentalities – the likes of the Shaiks, Gumedes, Singhs, Bennetts, Friedmanns, Malaysian developers and so many others who promote the Point and Durban, willy-nilly – is that the public subsidisation for these rascals draws off resources desperately needed in poorer areas. The other danger comes from the cementing of the Point gentrification fantasies – where, instead, the commoning, decommodification and deracialization of this extraordinary space is what a genuine post-apartheid democratic politics must seek.

1 Dovey, K. 2005. Fluid City; Transforming Melbourne’s Urban Waterfront, Sydney, Australia UNSW Press. [Clarify citation style. APA?}

4 Trotter, H. 2008. Sugar Girls and Seamen: A Journey into the World of Dockside Prostitution in South Africa. Johannesburg: Jacana, p. 110

5 South African Reserve Bank 2018. Quarterly Bulletin, June, p. 9.

10 Maharaj, B., A. Desai, and P. Bond (Eds) 2010. Zuma’s Own Goal. Trenton: Africa World Press.

11 Data are from the World Bank [?]. Also worrying is that in spite of lower global cross-border financial flows, South Africa’s economy is sinking quickly into ruinous foreign debt: $173 billion by mid-2018, a record 51 percent of GDP, 10 percent higher than when in 1985 the apartheid regime defaulted on overseas loans. In mid-2018, another world financial meltdown loomed in part because stock market jitters after Trump announced a multi-front trade war likely to include autos produced in Durban’s giant Toyota plant.

12 Xi Jinping 2015. “Xi Jinping Attends 7th BRICS Summit and Delivers Important Speech.” Moscow, 9 July. Beijing, Ministry of Foreign Affairs. http://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/topics_665678/xjpcxjzgjldrdqchwhshhzzzcy...

13 Bond, P., and A. Garcia 2015. BRICS: An anti-capitalist critique. Johannesburg: Jacana Media.

14 Xi Jinping 2017. “Keynote Speech to the World Economic Forum,” Davos, World Economic Forum, 17 January, https://america.cgtn.com/2017/01/17/full-text-of-xi-jinping-keynote-at-t...

16 Lefebvre, H. 2003. The Urban Revolution, trans. Robert Bononno (Minnesota University Press, Minneapolis, p. 159.

17 South African Reserve Bank, Quarterly Bulletin, p. 10. The first half of 2018 was miserable for property speculators, as the FTSE-JSE South African Listed Property Index collapsed by 18 percent. Anderson, A. 2018. “Listed property unlikely to shake off doldrums in 2018.” Business Day, 12 June. https://www.businesslive.co.za/bd/companies/property/2018-06-12-listed-p...

18 Harvey, D. 1989a. From managerialism to entrepreneurialism: The transformation in urban governance in late capitalism. Geografiska Annaler. Series B. Human Geography 71: 3–17.

19 Harvey, D. 1985. The Urbanization of Capital. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University.

20 Mkhize, N. 2015. Durban’s sought-after Point poised for new wave of development, Business Day, 17 August, http://www.bdlive.co.za/business/property/2015/08/17/durbans-sought-afte...

21 Peck, J. 2012. Austerity Urbanism, City: Analysis of Urban Trends, Culture, Theory, Policy, Action. Vol.16. pp. 626-55.

22 Basson, A. 2012. Zuma Exposed. Johannesburg: Jonathan Ball, p.292

23 Basson, Zuma Exposed, p. 294.

24 Basson, Zuma Exposed, pp. 295–296.

25 Basson, Zuma Exposed, p. 297.

27 Plaut, M., and P. Holden 2012. Who Rules South Africa? Johannesburg: Jonathan Ball, p. 224.

28 Johnson, R. W. 2010. South Africa’s Brave New World: The Beloved Country Since the End Of Apartheid. London. Penguin Books, p. 293. In May 2017, Khumalo finally lost a long legal battle over violating exchange control laws while negotiating a loan of more than $100 million with Deutsche Bank London. Khumalo had pledged shares bought from Harmony Gold in a black economic empowerment scheme to Deutsche Bank, which represented an illegal offshoring of his profits. He subsequently concentrated his efforts on Zimbabwean mining assets.

29 Bond, P. 2012. ‘Looting Durban.’ Counterpunch, 2 January, https://www.counterpunch.org/2012/01/02/looting-durban/

31 Peters, M. 1999. “Chairman’s death: street woman talks.” Independent on Saturday, 15 May. See also Desai, A. 2006. “Ways of (sight) seeing in KwaZulu-Natal,” Capitalism Nature Socialism, 17, 3, pp. 9–23. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/10455750600874498?scroll=top... and Jones, N. 2004, In the Public Interest, Doctoral Thesis, Faculty of Humanities, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, https://researchspace.ukzn.ac.za/bitstream/handle/10413/6825/Jones_Nicol...

32 But was this not an appropriate honor for Gandhi, that old rascal who turned celibacy into a sex scandal, choosing young women (including relatives) to lay naked with him in order to test his resolve? https://mg.co.za/article/2007-03-26-tempers-fray-over-durban-name-changes

33 Mandela, Charles and Simmer were also directors in Ocean Spray investments, which was awarded a tender by Msunduzi municipality to build the Camps Drift Waterfront development in Pietermaritzburg (the provincial capital, an hour west of Durban). It is a $250 million project to include canals, islands hotel and retail development as well as upmarket residential areas and an Olympic canoe and kayak slalom water course. Mandela, Masinga, and Henry are also directors of New Ground, which in 2018 was given the contract to build a hotel complex near Pietermaritzburg.

34 Harvey, D. 1999. The Limits to Capital, London, Verso, p. 369.

35 Khan, S. 2005. “52 Places to go in 2015.” New York Times, 11 January. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2015/01/11/travel/52-places-to-go-in...

36 Bond, P., and L. Browder 2018. “Deracialized nostalgia, reracialized community and truncated gentrification.” Forthcoming in Cultural Geography.

38 Spinnaker is named after ‘A large three-cornered sail, typically bulging when full, set forward of the mainsail of a racing yacht when running before the wind’ (Oxford English Dictionary). [Incomplete reference citation.]

39 http://www.saconstructionnews.co.za/8-infrastructure-projects/16780-contemporary-new-building-for-durban-s-historic-port-precinct

41 http://www.bdlive.co.za/business/property/2015/08/17/durbans-sought-after-point-poised-for-new-wave-of-development

42 Lawrence, D. H. 1964. The Complete Poems of D. H. Lawrence (Two Vols). London: Heinemann. [Editor?]

43 One student commented: “We have ‘graduated’, but with no practical experience, so in actual fact our graduation was not beneficial to us because our certificates are not valid until we obtain practicals.” Funds were “being siphoned off to service providers, especially of accommodation, which is a major cost of the programme amounting to about $50,000 per student.” amaBhungane 2017a. [Properly formatted?] ‘Transnet sold us false dreams.’ Daily Maverick, 6 January. https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2017-01-06-amabhungane-transnet-...

45 amaBhungane 2017b. ‘A third Gupta Transnet kickback contract unearthed,’ Daily Maverick, 18 September, http://amabhungane.co.za/article/2017-09-18-guptaleaks-a-third-gupta-transnet-kickback-contract-unearthed and https://www.news24.com/SouthAfrica/News/guptaleaks-kickbacks-for-transne...

47 The denialists were Christopher Everatt and John Zeitsman from ZAA and Roy van Ballegooyen from the state-funded Council for Scientific and Industrial Research. http://www.bdlive.co.za/business/transport/2014/01/20/transnets-durban-p...

52 Coastkzn 2018

53 Sky News February 24, 2018 https://www.iol.co.za/ios/news/shipping-company-admits-to-port-nurdle-ac...

54 Marx, K. (1964) Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts of 1844. Dirk Struik (trans.). New York: International Publishers, p. 717.

60 Bond, ‘Looting Durban.’ https://www.counterpunch.org/2012/01/02/looting-durban/

62 Harvey, D. 1989b. The Condition of Postmodernity. Cambridge, MA, and Oxford: Blackwell, p. 191

63 Zukin, S. 2007. David Harvey on Cities, pp. 102–120 in Castree, N., and Gregory. D., eds. David Harvey: A Critical Reader. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, p. 111.

64 Pilkey and Cooper, 2014: preface [?]

67 Pilkey, O., and A. Cooper 2014. The Last Beach, Durham: Duke University Press.

68 Pilkey and Cooper, The Last Beach.

71 Liebmann reached his peak, however, in 2018, when after creative disagreements and a miserable return on the portfolio, he was thrown out of Propertuity by new investors from Rand Merchant Bank. Muller, J. 2018. “Mr Maboneng Jonathan Liebmann moves on: Urban renewal developer Propertuity forced to restructure on the back of tough trading conditions and a change in strategy.” Business Day, 31 May. https://www.businesslive.co.za/fm/fm-fox/2018-05-31-mr-maboneng-jonathan...

73 Jacobs, J. ,[Specific text?] edited by S. Zipp and N. Storring. 2016. Vital Little Plans: The Short Works of Jane Jacobs. New York: Random House. [This citation looks unconsistent with others.]

75 Merrifield, A. 2014. The New Urban Question. London: Pluto Press, p.112

77 Gottdiener, M. 1994). The social production of urban space. Second edition, University of Texas Press, Austin, Texas, p.191.

79 In one case, Point protesters in 2014 worked in sync with the secondary circuit’s speculators, in the form of a march of local residents supportive of the Community Policing Forum, demanding “eradication of drugs, human trafficking and crimes” – with no reference to what is generally understood as widespread police corruption. http://journalismiziko.dut.ac.za/uncategorised/point-peaceful-march-to-fight-against-illegal-stuff/

87 Amisi, B., P.Bond, N.Cele, and T.Ngwane 2011. “Xenophobia and Civil Society: Durban’s Structured Social Divisions,” Politikon, 38, 1, pp.59–83.

88 Bond and Browder, “Deracialized nostalgia, reracialized community and truncated gentrification.”

90 Harvey, D. 2001. Spaces of Capital: Towards a Critical Geography. Edinburgh, Edinburgh University Press, p. 353.

91 Merrifield, A. 2006. Henri Lefebvre: A Critical Introduction. Routledge. New York, p. 83.