This special issue of Socialism and Democracy marks the centennial of W.E.B. Du Bois’s classic, The Souls of Black Folk. At the same time, going beyond our coverage of the Reparations movement in S&D #31, it deepens our commitment to implementing a thoroughly multiracial vision of the goals evoked by the name of this journal. The close link that exists in principle between the struggle against racism and the struggle for socialism was well articulated by Du Bois himself. One of the most celebrated assertions of his 1903 work was, “The problem of the twentieth century is the problem of the color line.” Revisiting that prophecy fifty years later, he wrote (citing Marx’s influence):

I still think today as yesterday that the color line is a great problem of this century. But today I see more clearly than yesterday that back of the problem of race and color, lies a greater problem which both obscures and implements it: and that is the fact that so many civilized persons are willing to live in comfort even if the price of this is poverty, ignorance and disease of the majority of their fellowmen; that to maintain this privilege men have waged war until today war tends to become universal and continuous, and the excuse for this war continues largely to be color and race.

Today, despite another fifty-year lapse, the relevance of these observations is undiminished. In the interim, while the long-term project of socialism still nurses the wounds bequeathed by its first nation/state-level embodiments, and while the “universal and continuous” character of the war waged by the privileged becomes even more pronounced, there are nonetheless hopeful signs of a revived popular movement cutting across hitherto formidable barriers of distance, language, and culture. Some of these signs have been recorded in our pages, with articles inspired by the anti-corporate- globalization movement and the World Social Forum (both in S&D #30), and by the World Conference Against Racism (S&D #31). Despite the severe obstacles posed by post-9/11 developments (especially in the U.S.), these movements continue to grow.

With our present focus on race and racism, while still keeping the global dimension clearly in view, we focus much more sharply on racism’s roots and ramifications within the United States. The general importance of such a focus hardly needs to be underlined, but some of the specific reasons for its urgency may be worth mentioning. In the first place, despite the important achievements of the Civil Rights movement, which reached a high point during the 1960s, it is clear that institutional racism remains deeply entrenched. The articles below help give a composite picture of this situation, which is manifested not only in continuing economic and social disparities, but also in the sometimes deliberate disfranchisement of oppressed communities (a notable factor George W. Bush’s “selection” as president), and in the global projections of U.S. imperial power. More recently, with the implementation of “homeland security,” discredited practices of racial profiling have been revived, as the ruling class has opted for discriminatory and repressive measures in preference to a reconsideration of its provocative geo- political agendas.

Taken together, these circumstances have in some ways raised the stakes of anti-racist political work. While such work has always been necessary for the oppressed as a matter of survival, and while it has also had, for other sectors, both the aspect of a moral imperative (going back to anti-slavery campaigns) and that of a strategic alliance (relative to labor organizing and to progressive social legislation), it is now becoming more clearly central to the survival of humanity as a whole. With the socialist project at an ebb and with the consequent almost completely unrestrained rule of corporate capital, both the need and the space for a popular movement of unprecedented scope and cohesion have become clearly apparent. Such a movement cannot afford the weaknesses of its predecessors, among which a failure to thoroughly address the “color line” was, along with comparable shortcomings vis-à-vis gender, perhaps the most devastating.

In any effort to overcome such weaknesses, dialogue of the kind that we are promoting in these pages will have an indispensable role.

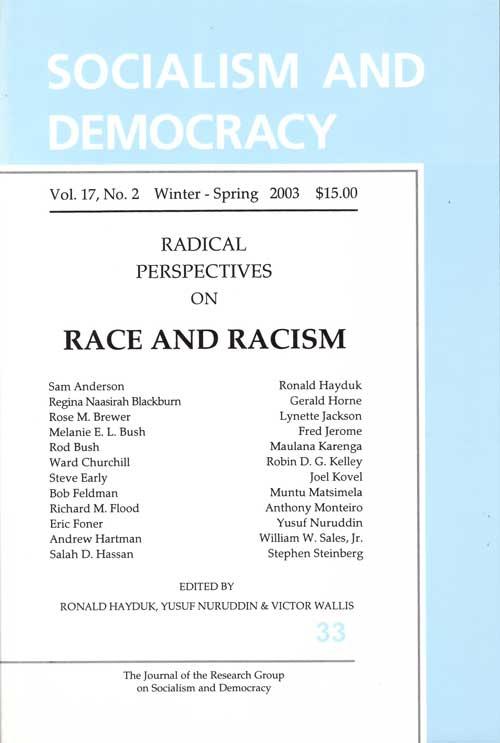

This collection had as its initial core a series of presentations at the Brecht Forum/New York Marxist School. Ward Churchill’s article is a greatly expanded version of such a talk; the articles by Eric Foner and by Gerald Horne, as well as the symposium on “Critical Black History,” are edited transcriptions that essentially retain their original format. The articles by Anthony Monteiro, Maulana Karenga, and Regina Naasirah Blackburn are revised from talks given at the symposium “The Color Line Then and Now: A Tribute to W.E.B. Du Bois,” which was the opening plenary session of the conference “Challenging the Color Line: Confronting Issues of Race and Class in the Era of Global Capital.” This conference was sponsored by the Brecht Forum and held at New York University in February 2002. We are grateful to the organizers of these events, especially Liz Mestres and Joel Washington, for facilitating our access to the materials.

Beyond these sources, we have ranged widely in our search for writings that would do justice to the immense scope of our subject. We wish to thank all those authors who responded to our special solicitations (in some cases, on rather short notice)—not only for their confidence in our project, but also for their cooperation throughout the editorial process. We trust that the importance of their contributions will inspire other writers to continue and extend, in future issues of Socialism and Democracy, the conversation that we have started here.